The Memorial of the Name.

An exhibition mounted at Sevilla House, Brechin Castle, in memory all who toiled in the sugar estates of Trinidad.

During these times of the Coronavirus pandemic, when schools in

Trinidad and Tobago and all over the world are closed, we would like to

take teachers and students on a virtual tour of the Museum of the Sugar Industry of Trinidad and Tobago, which was located at Sevilla House, Brechin Castle, in Couva and is currently

(as has been for a while) closed to the public.

You

can double-click on the images and enlarge them, and download them for

the information contained in them. We hope that you will take the

virtual tour and get a lot of information about the history of sugar.

The sugar cane industry shaped the landscape, the economy and the people of Trinidad and Tobago. Much of our development, culture and wide mix of peoples has had its roots planted deep in the sugar cane fields of the country. The over-arching purpose of Sevilla Sugar Museum is to honour and preserve the memory of the Trinidad and Tobago Sugar Industry, paying homage to all those who were involved.

The Museum of the Sugar Industry of Trinidad and Tobago was designed and built at Sevilla House, Brechin Castle in Couva, the heart of the Sugar Belt of Trinidad. Its exhibits and installations commemorate the men, women and children of the Sugar Cane era of Trinidad and Tobago, document the history of Sugar Cane production and development in Trinidad and Tobago. It was conceptualised to educate the citizenry and increase awareness about the economic, social and cultural aspects of sugar production, to act as the starting point for the collection and documentation of artefacts and ephemera related to the sugar industry in Trinidad and Tobago, and to preserve the site, and the history of the site, of Sevilla House.

The inaugural exhibit entitled "The Triumph of the People" is a photographic exhibit that pays tribute to those who toiled in the sugar cane plantations of Trinidad and Tobago. The exhibition attempts to bring to life and to give a name to the men, women and children of the sugar cane fields. This initial exhibit explores the work and social life attached to the sugarcane plantation. It strives to get the visitor to find a little piece of herself or himself in the faces and names of those who have gone before. The exhibit utilizes some never before published images of the sugar industry of Trinidad and Tobago, all of which are displayed in attractive and informative montages.

Some highlights of the exhibit include a commentary on the women of the sugar cane fields, while at the same time educating the public about the development of sugar in Trinidad and Tobago. The exhibit incorporates three-dimensionsal exhibits of tools and other devices that were characteristic of the sugar era.

The Museum of the Sugar Industry was opened on 5th August, 2015, by The Hon. Rodger Samuel, Minister of National Diversity and Social Integration. The museum exhibit was coordinated by Museum Consultant and Curator of the National Museum, Lorraine Johnson. It was conceptualised and built by Gérard A. Besson, HBM, D.Litt (h.c.) with material from the Paria Publishing Archives, and with items and images contributed by the former workers of Caroni (1975) Ltd. Consultants to the projects were Professor Brinsley Samaroo and Afsal Muradali. The installations of the exhibits were built by Peter Sorzano of Signs and Designs Ltd.

Double-click on the images to enlarge and read them!

Entrance Area: "The Memorial of the Name"

|

| Entrance to the Sugar Museum |

|

| This very large entrance panel is actually a Word Cloud, fashioned from some of the family names of East Indian indentured labourers who came to Trinidad in the mid-19th century. Double-click on the image to enlarge so you can read those names. |

|

| Oxen Yoke - A tribute to those who labored in the fields |

We are all here because of sugar, symbolized by this yoke. The yoke, once put on bovines for transporting sugar cane, is a reminder of the immense toil that was required to produce sweet table sugar. People who came to Trinidad and Tobago, free, enslaved or indentured, to work in the cane fields have shaken off the yoke and triumphed over a history that had an inauspicious beginning for so many. Today, the sugar industry is gone, and it is only the names of our ancestors that we carry forward into the future that make us remember this triumph.

|

| Sharpening stones, water stones or whetstones used to grind and hone the edges of steel tools and farm implements. The sharpening stone seen on the terrace is one of the many that could be found at Brechin Castle. Workers brought their cutlasses on a morning to be sharpened. It is said that the wheel was turned by women who were pregnant and could no longer work cutting the cane until their confinement. |

|

| Exhibit of models of carts used to transport canes. |

|

| The entrance to Room 1. |

As you turn left from the entrance area, you will see two large panels that will give you some astonishing information. On the left is a panel depicting the extensive rail system that once existed in Trinidad. Built over many decades to facilitate Trinidad's expanding agricultural economy and, to link towns and villages, it transported people and a variety of agricultural produce, it opened the deep countryside, linking it to the urban centres and to the capital. The sugar estates also had a rail system that transported sugarcane to the factory. Double-click on the panel below and enlarge it to read.

|

| Trinidad once had an extensive railway system, of which nothing remains today but a few disused bridges. |

To the right of the door you can see an infographic of a snapshot of the agricultural and livestock sector of Trinidad in the mid-1950s, just before Independence. It will surprise the visitor that just a few decades ago, Trinidad and Tobago had such flourishing agriculture, with hundreds of thousands of animals, millions of chickens, and massive production of all sorts of crops. (Double-click to enlarge and read).

|

| Trinidad's entire society was geared to nourish, maintain and sustain agriculture, employing hundreds of thousand, feeding the colony, and creating crops for export. |

Double-click on the images to enlarge and read them!

Room 1: "Woman in the Cane"

|

|

The bell of Felicity Estate was founded in 1820 & is now 200 years old! It was last seen in the general office at Brechin Castle.

|

The sound of the bell and the call of the conch shell summoned the woman in the cane. This brass bell once rang on the Felicity Hall sugar estate. Made in 1820, 18 years before the emancipation of the slaves, it sounded for enslaved African men and women from 1820 to 1838 and for the East Indian indentured, from 1845 to well into the 20th century, all of whom laboured and struggled in the cane fields of the Felicity plantation. It is a powerful symbol of an experience shared by people who lived and toiled on that estate and, on all the other estates to which they were either chained or bounded. Its ring rang out before the rising of the sun to mark the commencement of work, sounded for breaks for food or emergincies and for the return to the barrack range at sundown.

It is one of the few relics in existence in T&T that transcends both slavery and indentureship and should be preserved with care.

|

|

| Details of the "Floating Panels" reflecting the tiled floor. |

|

| Details of the "Floating Panels" reflecting the tiled floor. |

|

|

Details of the "Floating Panels" reflecting the tiled floor.

|

|

|

| The bases of the "Floating Panels" during construction. |

|

| "Floating panels" in place. |

|

| The reflective bases of the Floating Panels give an impression of being transparent. |

|

| View from the bell shows the how the curved Floating Panels symbolise the sound of the bell going out over the estate. |

Walking through the arched doorways, you now enter a room where the exhibits seem to float over the beautifully-tiled floor.

This room is dedicated to "Woman in the Cane", as part of the evolving demographic of Trinidad and Tobago against the backdrop of the Sugar Industry. From the late 18th century and well into the 20th, women toiled in the cane fields of Trinidad and Tobago. For the first 55 years, this was the enslaved African woman - from the beginning of the plantation economy in 1783, to the Emancipation of the slaves in 1838. Then, for more than 100 years, from 1845 well into the 20th century, the Indian woman worked in the cane. The Indian presence in the cane continued up to 2003, when the sugar industry in Trinidad and Tobago came to an end. Portuguese and Chinese women also came in the mid-19th century. Their number, small, has hardly left a trace.

The exhibit shows the diversity of the experience of the tens of thousands of women who came to Trinidad and Tobago to work in the sugar industry. They suffered in the relentless heat and grueling workload in the sugar fields. They made homes in the barracks of the plantations, bore children and raised families, and found the strength in themselves to create Trinidad and Tobago's enduring culture.

The exhibits featuring women on various sugar estates around the country are "sound-wave" shaped, symbolising the clanging sound of the estate bell that dictated the rhythm of life in the cane.

|

| Detail of the Champs Elysées (Maraval) sugar estate panel in the installation. |

|

| Champs Elysées estate was the residence and property of Jean Valleton de Boissière in Port of Spain. The panel shows a scene from Champs Elysées flanked by portraits of women, all drawn by Richard Bridgens in the 1820s. Bridgens is the only source of authentic, contemporary images of people of African descent in Trinidad and Tobago during the times of slavery. |

***

|

| Detail of the Rose Hill (Port-of-Spain) sugar estate panel in the installation. |

|

| Rose Hill estate in east Port of Spain was the residence and property of Edward Jackson, giving names to Rose Hill Road and Jackson Place. |

|

| Detail of the Peschier (Port-of-Spain) sugar estate panel in the installation. |

|

| The Peschier estate in St. Ann's is today the location of the Queen's Park Savannah, Botanical Gardens and President's House in Port of Spain. |

***

|

| Detail of the St. Clair (Port-of-Spain) sugar estate panel in the installation. |

|

| St. Clair sugar estate was the property and residence of Alexander Gray, who named his house there Sweet Briar House. Gray Street and Sweet Briar Road are named for these. |

***

|

| Detail of the Children of the Cane panel in the installation. |

|

|

| After the abolition of slavery in 1838, and with the beginning of indentureship in 1845, the face of the Woman in the Cane changed from African to Indian. This panel commemorates the children of the women in the cane fields who grew up amongst much hardship. |

***

|

| Detail of the Home Life panel in the installation. |

|

| The life of the Woman in the Cane was, in the 19th century, built around the home. This panel shows women engaged in the making of roti, an "ajoupa" typical of the time, and some interesting information regarding marriage and language. |

***

|

| Detail of the Body and Baigam panel in the installation. |

|

| Bodi and baigam, melons and ... careers: this panel shows how the women in the cane also supplied fruit and vegetables to the surrounding countryside. A list of occupations in which men and women of Indian descent were engaged in 1931 shows how careers were forged from humble beginnings by the children and grandchildren of the indentured cane workers. |

***

|

| Detail of the Palmiste estate panel in the installation. |

|

Palmiste estate in San Fernando was the property and residence of Sir Norman Lamont. This panel talks about the school

system for the children of the cane in the 19th century, and the establishment of the Canadian mission schools. |

|

| Aranguez, Buen Intento, El Dorado, Les Efforts, Ne Plus Ultra, Plein Palais, Brechin Castle, Retrench, Wellington, Paradise, Endeavour. The names of sugar cane estates in Trinidad and Tobago speak of the island's heterogeneous population. This panel discusses the relationship between the Woman in the Cane and the all powerful estate manager. |

|

|

| Detail from the panel above it shows some British silver coins from which jewellery was made for the Woman in the Cane. |

|

| Passage to India: This panel features the average ratio of women to men during the years of Indian indentureship in Trinidad and Tobago. |

As you come to the end of the "Woman in the Cane" exhibit, you will see a real-life, a bit rusty, sky-blue, mid-20th century gentleman's bicycle on display in a showcase. This bicycle was brought to Sevilla House during the construction of the Museum by the family of a former Caroni worker, Mr. Ganesh Kissoon. It is an important contribution, since the bicycle shed of the now derelict sugar factory at Brechin Castle once housed space for hundreds and hundreds of bicycles of the workers who pedalled to and from work every day.

|

| This bicycle was donated by the Kissoon family in memory of their father Ganesh Kissoon, born 1943, died 2009. He worked at Esperanza Estate as a crane operator. This exhibit is the first donation to the Sugar Museum at Brechin Castle. |

Double-click on the images to enlarge and read them!

Room 2: "We are all here because of .... SUGAR!"

As you retrace your steps and enter the second room of the Sugar exhibit, you will be greeted by a model of a sugar molecule:

|

| This model shows the molecular structure of the sucrose, the basic building block of sugar. Sucrose is a disaccharide, made up of two monosaccharide molecules: a glucose molecule and a fructose molecule. Its molecular formula is C12H22O11. (Thanks to Zoë Hart and Alice Besson for making this molecule). |

|

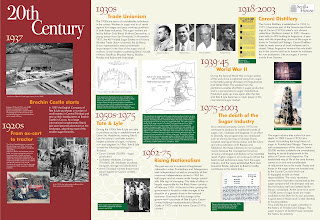

To your right is an illuminated, large panel entitled " Sweet Sorrow: The Timeline of Sugar in Trinidad and Tobago".

|

| The detailed timeline of Sugar in Trinidad and Tobago. |

|

| "We are all here because of Sugar". |

Turning left, you will see the expanse of the room beyond the sugar

molecule. This section of the Museum is dedicated to "We are all here

because of Sugar" and pays homage to the various non-Indian population groups who

were brought and came to Trinidad and Tobago to work in the Sugar

Industry: Africans, Chinese and Portuguese.

However, this

section starts out with the original inhabitants of these isles, and

remembers the First People: "The Vanishing Amerindian".

Exhibit 1: The Vanishing Amerindian

|

| The Vanishing Amerindian exhibit. |

|

| Detail of the display, showing the see-through nature of the panels. |

The exhibits in this section of the room are beautifully constructed by Peter Sorzano of Signs and Designs, following the concept by Gérard A. Besson. Each stand has a large backdrop with an image symbolising the population group that the exhibit is dedicated to, and two see-through, seemingly floating panels in front of it. The entire installation symbolises the fleetingness of fate and the people who moved at different times, in different spaces, some leaving important cultural footprints—such as Amerindian place names for rivers, mountains, and towns— while the lives of others are just a whisper in the wind.

|

| This is one of the oldest photographs of a member of the First People in Trinidad and Tobago. We overlaid it with the names of tribal chieftains of the early Spanish colonisation of Trinidad, which have come down in history to us. |

|

| The first of the see-through panels features the pre-historic petroglyph found in the forested mountains of Trinidad's Northern Range. Nobody knows what exactly it wants to convey. |

|

| The second floating panel of this exhibit shows an illustration of pearl diving in the Gulf of Paria, where thousands of First People lost their lives, giving the Gulf its second name, "Gulf of Tears". |

Exhibit 2: Pancho Campbell, Freed African

|

| The Pancho Campbell exhibit. |

|

| Detail from the Pancho Campbell exhibit. |

The second floating installation is dedicated to Pancho Campbell, the Freed African and who settled in Tobago. African slavery was abolished in the British Empire in 1807, but the other colonies and nations in the New World continued the practice for several decades after. Pancho was a man abducted by African traders in 1850, and sold to a Portuguese ship. En route to the Americas, a British frigate of war captured the slaver and took all Africans in her hull to safety. Pancho Campbell settled in Tobago, where he lived to 115 years.

|

| A photograph of Pancho Campbell over an antique map of the African continent. |

|

| The first floating panel gives the detailed story of Pancho Campbell, alongside a map of West Africa with names of the tribal origins of African slaves in Trinidad and Tobago. The background shows a word cloud of documented slave names in Trinidad. |

|

| The second floating panel on this installation gives statistical data on the enslaved African population of Trinidad between 1782 and 1803, with a slave census of 1813 that has a breakdown of the tribal origins of the enslaved. |

Exhibit 3: African Slavery in Trinidad and Tobago

|

| Stocks for Hands and Feet: A life-size replica after a sketch by Richard Bridgens, 1820s. |

The central exhibit of this room you can hardly miss: a life-sized torture instrument called "Stocks for Hands and Feet". It was built after a sketch by Richard Bridgens from the 1820s. The stocks, common throughout Europe as punishment for various misdemeanours in the Middle Ages, were used in Trinidad to punish slaves, who were put into them by the overseers or masters of the estate and left to suffer in the tropical sun for days. To actually see a life-size replica of one of the many torture instruments used on the enslaved Africans gives a different impression than just to read about them or see them as pictures, and reminds the visitor of the very real suffering that millions of our ancestors in the Caribbean have endured.

|

| The large curved panel commemorating the enslaved African people who worked in the sugar cane industry in Trinidad and Tobago. |

Here are the segments of the panel so you can double-click on them and read the text.

|

| The left side of the panel "African Slavery". |

|

| The centre part of the panel. |

|

| Right side of panel. |

Exhibit 4: Chinese Indentureship

|

| The installation commemorating the indentured Chinese who came to Trinidad to work in the Sugar Industry. |

|

| Detail of the Chinese Indentureship exhibit. |

Even before the abolition of the slave trade in 1807, and emancipation in 1838 the British colonial government was looking around in its Empire for cheap labour to work the sugar estates. One source was China. The first ship from China, the "Fortitude" had in fact arrived in 1806. In the 1850s and 60s, eight ships brought 2,645 indentured Chinese workers to Trinidad.

The first Portuguese indentured labourors to come to Trinidad came from the Azores in 1834. Organised indentured immigration of Portuguese from Madeira began in 1846, with about 1,300 people arriving overtime. The ship "Senator" was amongst the earliest ships to transport Portuguese indentured workers to Trinidad. Indentured Portuguese also came from Madeira, Cape Verde and Macao.

|

| The backdrop of the installation about Portuguese Indentureship shows an original photograph of the time, where two Portuguese brothers bid goodbye to their third brother, who is embarking on a boat to come to the New World. In the background is an old map of the Atlantic Ocean. The photographers mark at the bottom (A. Cavalho, Funchal, Madeira) shows were many of the Portuguese indentured labourers came from. |

|

| The see-through panel is a memorial to Portuguese names of immigrants who came to work in the Sugar Industry, and pictures of Portuguese ancestors from long ago. It gives a short summary about the history of Portuguese Indentureship in the island. |

|

| The third panel of the Portuguese installation shows more photos of the faces of Portuguese immigrants, and honours José Bento Fernandes, who was the only descendant of a Portuguese immigrant to acquire a sugar estate (Forres Park). |

This brings us to the end of the Virtual Museum of the Sugar Industry of Trinidad and Tobago! We hope you enjoyed your walk-through. In the end, we are all here because of sugar. Wherever the ancestors of Trinidadians and Tobagonians hail from in the world, they came here to work in the sugar industry.

With this Museum, we honour them by establishing a memorial to their names, and many visitors would have recognised their own name or those of their family, friends and acquaintances in Trinidad and Tobago. African names, Chinese names, Portuguese names and Indian names have all become threads that make up the fabric of the country, and the place names of the First People grace our landscape. While the sugar industry has come to an end and Brechin Castle, once one of the largest sugar factories in the world, lies in ruins, we must not forget the people who toiled in the sun to bring about this sweet—and sorrowful—commodity that the world enjoys today.

|

| Sevilla House at Brechin Castle, festively illuminated to celebrate the opening of the Museum of the Sugar Industry in 2015. |

|

| Sign at the Sevilla House Sugar Museum. |

Thank you and come again!