Christopher Columbus approached the island that he would name for the Holy Trinity out of a

rolling Atlantic Ocean from the north-east. To persons sailing from Barbados, for example, who would want to enter the Gulf of Paria from the Serpent’s Mouth, Trinidad would appear at first, in the distance, as a long mountain chain, pale and blue, that stretched ever westward. As one dropped to a more southerly course, another pale blue mountainous shape emerges on the horizon some way away from the first, and further south, a smaller range of hills would be seen. There would be a point in time when all three ranges, the northern, the central and the southern, separated by wide valleys, would appear on the horizon, joined at their bases by the land.

E.L. Joseph writes “Columbus rightly describes the north-eastern promontory of the island as resembling a galley under sail; hence he called it Punta de la Galera (Point of the Galley), which name it bears today. As he advanced towards the island from eastward, the three points which he first described in his log were doubtless Punta de la Galera, Point Manzanilla, and Point Guatare. He then coasted five leagues to the southward, where he anchored at night, doubtless in Manzanilla Bay. On the following day, the 1st of August, he passed what is now called Point Galiota, which is the southeast point of the island, and ran before the wind to the westward, along the channel, in search of a convenient harbour and water.”

|

| For close to three hundred years Trinidad was under the rule of Spain |

Based on the location, it has been questioned as to whether Perez could have seen three separate peaks, presumably Morne Derrick, Gros Morne and Guaya Hill, as separate from the rolling mass of hillsides that comprise what we know today as the Trinity Hills.

Joseph continues, “Anchoring at a point, which he called Punta de la Playa, he sent his boats on shore for water. Here the seamen discovered an abundant limpid stream; this is conjectured to be the Marouga river.”

Columbus’ men came ashore at several points along the southern coast. Alarmed by the strength of the currents he called this entrance of the Gulf Boca de la Sierpa. He may have lost an anchor there, as one was found, some centuries later, that fitted the description of anchors from that time.

Before him lay the vast expanse of the Gulf of Paria, which he explored and named the Gulf of Whales, Gulfo de Balina. Never imagining that he had come upon the continent of South America, he called the vast coast from which a massive river, the Orinoco, flowed into the gulf, the Island of Gracia.

|

| A16th century chart of Trinidad & Tobago. Cambridge. |

Columbus and his sailors would have been on the lookout for the evidence of gold, as this was foremost in the minds of those who had risked their lives on these perilous voyages. The first recorded evidence of seeing a golden object here in Trinidad was when he landed at Point Arenal. There, according to Joseph, he was met by an Indian Cacique, who took the Admiral’s cap of crimson velvet off his head and replaced it with a circle of gold that the he himself had worn.

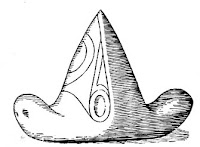

The cupidity, or greed, of the Spaniards was aroused further by observing the great quantity of pearls that the Tribal People wore and the plates of inferior gold, shaped like a crescent, that was also worn. These were called ‘guanin’ or ‘caracol’ and consisted of eight parts gold, six parts silver, and eight parts copper. The Indians said these came from the high-lands, which, they pointed out, was to the west. They cautioned that it was dangerous to go into the interior of the land, the mainland, “either because,” writes Columbus, “the inhabitants were cannibals” or the place was infested “with noxious animals”.

The 15th and 16th centuries were to see explorers, adventurers and exploiters come to these islands. As in the European wars of the period, payment, in fact profit, for these enterprises could only be had through the plundering of the conquered.

|

| Carib carbet left open to show hammocks. Baccassaas with one mast. Paddle. Carib pirogue. Caracol, a personal decoration worn by men made of a mixture of gold, silver and copper. |

It was the captains and the fighting men of the Reconquista, Spanish for the “reconquest”, who were at the forefront of the conquest of the New World. In ‘Companions of Columbus, Alonso de Ojeda’ we see, “. . .Letters were received from Columbus giving account of the events of his third voyage, especially of his discovery of the coast of Paria, which he described as abounding in spices, in gold and silver, and precious stones, and, above all, in oriental pearls, and which he supposed to be the borders of that vast and unknown region of the east, wherein, according to certain learned theorists, was situated the terrestrial paradise. Specimens of the pearls, procured in considerable quantities from the natives, accompanied his epistle, together with a great sensation among the maritime adventures of Spain. . .”

On the night of the 2nd, according to E.L. Joseph (1838), “a remarkable swell occurred which alarmed the crews exceedingly.” This swell is occasioned by a change in the tide which causes water to rush into the Gulf of Paria. This current—later called La Remou—caused the anchor of the Vaquenos to be severed from its cable and it was lost. The soil at Icacos is mainly sand and silt deposited over thousands of years by the Orinoco floods, so the spot where the anchor was lost became dry land.

| |||

| Christopher Columbus arriving in the New World. Daniel. |

The Conquistadors

|

| The Gulf of Whales was colloquially called the Gulf of Pearls, and eventually the Gulf of Tears for the hundreds of Tribal People who died there having been made to dive for pearls. |

The first attempt to settle the island of Trinidad was mounted in 1513, when two Spanish Dominican missionaries arrived. Their names were Francisco Cordova and Juan Garces, and they were successful in befriending the local Caciques, even though they didn’t know each other’s language.

When a Spanish ship arrived, the Tribal People, now used to the Spanish friars and trusting them, welcomed the sailors with tokens and gifts. A number of Amerindians were invited on board and no sooner had they arrived, that the captain raised anchor and set sail for Santo Domingo, where they were sold into slavery.

The Spanish friars, as upset as the Amerindians, and just short of being lynched by the Tribal People, begged to be allowed to try to free the abducted. With the next ship to arrive, they sent their complaints to the authorities in Santo Domingo and to the superior of the Dominican order. Unfortunately, the Amerindians from Trinidad had been bought as slaves by officials of the supreme court, so nothing was done about the matter. For eight months, the Tribal People and the monks waited in Trinidad. Eventually, the Amerindians lost their patience and the friars were put to death, becoming the first martyrs of their faith in Trinidad.

In 1516, Juan Bono from the Bay of Biscay arrived in Trinidad with 70 men. Ostensibly a peaceful settler, he won the trust of the Amerindians. After a while, Bono invited a large group of Tribal People to a feast of friendship. When everyone was gathered in a large hut, Bono’s men surrounded the hut, overwhelmed the gathering by force and abducted many of the Tribal People, taking them to their ship. The ones he could not fit into the hold were burnt to death inside the hut which was set on fire. Those aboard were sold as slaves in Puerto Rico.

Don Antonio Sedeño may be described as a conquistador and was the first governor of Trinidad

|

| An encampment of Tribal People in the Windward Islands in the 18th century from Brian Edwards’ “History” |

His arrival in 1530 marked the first serious attempt by the Spanish Crown to settle in Trinidad after its discovery by Columbus some 32 years before.

Prior to, and during his tenure, sporadic visits had been made by Spanish captains, who had tricked or forced the Tribal People they came into contact with to dive for the pearls in the Gulf of Paria. In order to find enough pearl oysters, the Indians were often forced to descend to depths of over 100 feet on a single breath, exposing them to the dangers of hostile creatures, waves, eye damage, and drowning, often as a result of shallow water blackout on resurfacing. This exploitation of the simple eventually led to their enslavement and the taking them away to the other pearl islands of Cubagua, Coche and Margarita. The death toll was so horrendous that the Gulf of Whales became known as the Gulf of Tears.

Sedeño arrived in Trinidad in November 1530, with two caravels, 70 men, food, arms, horses, domestic animals and trinkets for barter with the Tribal People.

|

| A drawing of Tribal People in the Orinoco delta in the 1800s. Shim. |

The Tribal People of Tobago, whose make up were not substantially different from their brothers in Trinidad, also had a dramatic encounter with Europeans. In the case of Tobago, which possesses the unfortunate history of being the most fought over island in the Caribbean, the Tribal People’s existence from very early on was one of misfortune. Nevertheless we learn from archaeologists of their long and substantial presence there. Mention is made of an “Indian Town” and several villages that were marked on early maps as the residences of kings. These Caciques have been named as Cardinal, Peter and Roussel. Roussel may have been a Frenchman who married an Amerindian woman. In all, the native population of Tobago in the 18th century appears drastically diminished as a result of not only the invasions, but also because of the rapid agricultural development that took place all over Tobago. It is said that by 1779 King Peter and his people had all left Tobago for the mainland. Dr. Boomert tells us that Tobago, like Trinidad, held a tribal presence in what is called the archaic period, which is about twelve thousand years ago. Pottery, tools and other evidence of their presence may be found at Milford Bay. Later, other people left their mark at Golden Grove, Great Courland Bay, Lover’s Retreat, Sandy point and in other sites all around the island. Today a visit to King Peter’s Bay on the leeward coast would be a gentle remainder of a turbulent past.

The Amerindians did not resist him. Rather, they came to welcome him, with their Cacique Maruana as the leader. Sedeño distributed gifts, and Maruana made him understand that he would appreciate him as an ally against the Caribs.

Sedeño, who was, however, cautious, built a fortification for his men and his possessions. After a while, the Spaniards’ food stocks began to run out. They decided to raid the conucos (villages) of the Amerindians in the northern part of the island, at Cumucurapo, in the dead of night. When the Amerindians heard of this, they conspired to expel the intruders—all with the exception of Maruana, who had come to see himself as Sedeño’s friend and did not join the conspiracy.

The attack of the Amerindians was sudden, but the Spaniards were able to hold them off for a while thanks to their fortifications and firearms. After losing many soldiers, Sedeño decided to retreat, sending the remaining men to the mainland and going himself to Puerto Rico for reinforcements and food. Maruana helped the Spaniards to escape in the two caravels in which they had arrived.

It was not as easy as expected for Sedeño to raise men and provisions in Puerto Rico. Everyone there had heard of the conflict with the Tribal People in Trinidad and was reluctant to join Sedeño. Over the next six years Sedeño travelled between Trinidad, the forts on the South American mainland, Puerto Rico and Santo Domingo. Fort Paria, which was where the remainder of the Trinidad soldiers had settled, was taken over by another Spanish conquistador, Diego de Ordas. Unbeknown to them, Sedeño sent a ship to Fort Paria with supplies. Fearful of de Ordas, the caravel turned away from the fort and landed instead in Cumucurapo. The Amerindians seemed to be welcoming enough, and gave the 30 men of the ship a place to settle. A week later, 24 of the sailors were killed by the Tribal People, who obviously did not trust the Spaniards. Six men escaped with the caravel and left to report to Sedeño.

|

| The El Dorado or golden man being overed with resin and sprayed with gold dust. Taken from an old engraving redrawn by Peter Shim. |

El Dorado, Spanish for “the golden one”, originally El Hombre Dorado (the golden man), or El Rey Dorado (the golden king), was the term used by the Spanish Empire to describe a mythical tribal chief of the Muisca native people of Colombia, who, as an initiation rite, covered himself with gold dust and submerged in Lake Guatavita. The legends surrounding El Dorado changed over time, as it went from being a man, to a city, to a kingdom, and then finally an empire. A second location for El Dorado was inferred from rumors, which inspired several unsuccessful expeditions in the late 1500s in search of a city called Manõa on the shores of Lake Parime. Two of the most famous of these expeditions were led by Sir Walter Raleigh. In pursuit of the legend, Spanish conquistadors and numerous others searched Colombia, Venezuela, and parts of Guyana and northern Brazil for the city and its fabulous king. In the course of these explorations, much of northern South America, including the Amazon River, was mapped. By the beginning of the 19th century most people dismissed the existence of the city as a myth. (Wikipedia)

At the end of 1532, Sedeño sailed once again to Trinidad with 80 men with a plan to attack the Amerindians. The Tribal People, however, had been warned of the night attack, and fought fiercely. However, Sedeño eventually overwhelmed them, leaving merely a handful of women and children in Cumucurapo, who fled into the mountains. Nothing was left of the village, and having no provisions, Sedeño withdrew to Margarita. A year later, Sedeño returned with 170 men with the intention to conquer and settle Trinidad. The Spaniards built a stockade at Cumucurapo. Many of his men fell ill, and even though he suspected another attack, Sedeño could only rely on the food supplies from the Cacique Maruana, so he decided to wait.

On the 13th September 1533, the second battle of Cumucurapo began. The tribes swept down from the mountains with loud battle cries. Many Spaniards were killed, and the Indian attack was only broken up when the Spaniards counter-attacked on horseback (a sight totally unknown and surely quite terrible to the Indian warriors).

Sedeño prevailed, rebuilt the fortifications, and motivated the remaining men. Several months later he was forced to give up, as many of his captains left to seek the riches of Peru with Pizarro. On the 27th August, 1534, Sedeño left Trinidad and never returned.

The legend of a golden man who ruled a city of gold had its origins in the tales told by the earliest travellers and explorers who had heard from the Tribal People of fabulous cities far into the deep forest of the mainland, or Terra Firma as it was called. These stories gained traction as the news of the success of the conquistadors, Cortes and Pizzaro, in Mexico and Peru became known. The idea that a third great, rich and vulnerable empire lay somewhere in the higher reaches of the Orinoco river became an obsession in the minds of many.

This was to shape the future of Trinidad and have a deadly effect on the Tribal People of Iere. Trinidad became the launching-pad for expeditions of no return. Don Antonio Sedeño’s tenure as governor was followed by Don Juan Ponce who arrived in 1571. His stay was short as he was met with hostility. He suffered the loss of most of his men as a result of illness and the attacks by the Tribal People on his encampment at Cumucurapo. Nevertheless his tenure as governor of Trinidad lasted until 1591.

The third Conquistador, Don Antonio de Berrio y Oruña, inherited from his wife María de Oruña, the maternal niece of the adelantado Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada, his many estates in what is now Venezuela. This included properties in Trinidad. He was appointed governor here in Trinidad in 1592 and held this title until his death 1597. His goal in life was to discover the fabulous city of El Dorado. He established the town of San José de Oruña on the banks of the Caroni river, as Port-of-Spain was little more that a fisherman’s hamlet in which lived Tribal People who had survived the depredations of the recent past. San José de Oruña was de Berrio’s base camp for the several expeditions mounted in his quest to find El Dorado, which he of course never did.

Upon his death in 1597 he was succeeded by his son Fernando who, like his father, quested for El Dorado. On these journeys, first to Trinidad and then into the vast and intractable interior of the South American hinterland, their obsession for gold and their cruelty to the Tribal People was met, at times, with terrible revenge.

Bartolomé de las Casas, 1484–1566, was a 16th-century Spanish historian, social reformer and Dominican friar. He became the first resident Bishop of Chiapas, and the first officially appointed “Protector of the Indians”. His extensive writings, the most famous being ‘A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies’ and ‘Historia de Las Indias’, chronicle the first decades of the Spanish colonisation of the West Indies and focus particularly on the atrocities committed by the colonisers against the indigenous peoples. Professor Bridget Brereton in “Book of Trinidad” tells us that “With the foundation of San José de Oruña, St Joseph, in 1592, Trinidad had been given the formal structure of a Spanish colony.” Little is actually known about the condition of the Tribal People in the decades that follow the arrival of the conquistadors and slave raiders. It was believed at the time that “the conversion of the Indians is the principal foundation of conquest.”

Dr. K.S. Wise of the Trinidad Historical Society tells us in the foreword to “Hyarima and the Saints’”, a play by F.E.M. Hosein (1976), that “The old historical records still in existence give full sanction for the existence of the great Nepuyo Cacique, Hyarima, for his failure to obtain armed assistance from the Dutch at Tobago in 1636, for the deep desire to rid Trinidad of the hated Spaniards and for placing his village on the site now occupied by the town of Arima.” The Arena massacre or Arena uprising took place in 1699 at the mission of San Francisco de los Arenales in east Trinidad. It resulted in the death of several hundred Amerindians, of several Roman Catholic priests connected with the mission of San Francisco de los Arenales, of the Spanish Governor José de León y Echales, and of all but one member of his party.

The Tribal People were pursued by the Spaniards who overtook them at Comcal and drove them to Cocal. Many dived into the sea in preference to being captured. Eighty-four rebels were captured and sixty-one of them were shot. The surviving Tribal People were interrogated via torture. Many of the tortured revealed that they were often beaten by the priests for not attending church services. The twenty two identified as ringleaders were hanged on 14th January, 1700, at San José de Oruña, the capital of the colony, and their dismembered bodies displayed. The women of the tribe were distributed among the Spanish households as servants.

|

| A Carib coulecure or manioc strainer with weight hung on it. |

|

| Carib pannier or basket. |

|

| A Carib mace or club. |

The Encomiendas

By the 1650s the Tribal People of Trinidad were being parceled out in encomiendas. The encomienda was a labour system, rewarding conquerors, conquistadors, with the labour of a specified number of natives from a specific community, with the indigenous leaders in charge of mobilising the assessed tribute and labour. The Spanish encomenderos were to take responsibility for instruction in the Christian faith, protection from warring tribes, suppressing rebellion against Spaniards, protection against pirates, instruction in the Spanish language and development, and maintenance of infrastructure. In return, the natives would provide tributes in the form of metals, maize, wheat, pork or any other agricultural product. In the first decades of the Spanish presence in the Caribbean, Spaniards divided up the natives, who in some cases were worked relentlessly.

The old Spanish families in Trinidad, that is, those dating back to the time of the conquistadors, had been granted large tracts of land in which villages had been established. The first encomiendas were Acarigua, San Juan, Arauca, Arouca, Tacarigua and Caura. An excerpt from a report by Don Domingo de Vara to the Spanish king in 1595 says: “The Indians for their labour will gain instruction in the matters of Our Holy Faith and shelter and protection, as though our children, so that they may recognise and appreciate the great work which our Commander does in bringing them to the obedience and protection of His Majesty. From this, those who wish to go will learn that we intend to populate these lands and not to depopulate them; to develop them and not to exploit them; to control them and not to destroy them. Those who do not accept this are warned that they will suffer the anger of God who has clearly shown that those who rob and maltreat the Indians, perish in the land they try to desolate, and their riches, acquired by deceit and tyranny, are lost in the sea and their families perish and are forgotten.”

Brereton tells us, “Outside of the encomiendas, where some six hundred Indians may have been living in 1712, there were many more living in the forest in independent settlements. To bring these ‘wild Indians’ under Christen influence and Spanish control, Capuchin missionaries were given the task of converting them between 1687 and 1708, and they established mission settlements, some of which survived as Indian villages well into the 1700s. The missions of the Catalan Capuchin priests (1687-1708) were at Acarigua, Tacarigua, Arouca, Arena, Montserrat, Savonetta, Mayaro, Guayaguayare, Naparima, Savana Grande, (Princes Town), and Maruga. Those of the Aragon Capuchin priests of Santa Maria (1758-1837) were at Port-of-Spain, Toco, Arima, Salabia, Matura, Acarigua, Tacarigua, Montserrat, Savonetta, Naparima, Savana Grande (Princes Town), and Siparia. The missions were abolished in 1708 and the encomiendas in 1716, but by then the great majority of the island’s Indians had become ‘Hispanised’; that is Christian, Spanish speaking, and organised into villages under some control of the church, of the Government, and of Spanish settlers who used them as laborers on the estates. By 1765 Trinidad’s population was estimated at 2,503, with 1,277 of these Christianised Indians.” And from Dr K.S. Wise we learn (op.cit.), “So also the historical records attest that Nepuyo Indians were collected in 1784 from Tacarigua, Caura and Aruca and added to the Mission at Arima under their own Corregidors, that this Mission became the principal one in the north where the devotion and unceasing labours of the Fathers brought to these Carib Indians the spiritual advantages of divine origin”.

The Cocoa Pañols

In Daniel Hart’s “Historical and Statistical Review of Trinidad”, the Tribal People’s presence averages between 1,200 to 1,500 persons between 1797 and 1817, with a high point of 1,804 in 1812. Then there is a steady decline to 571 in 1836, with none recorded by 1861.

There is evidence, however, such as in the writings of Dr. Pedro Valerio, who wrote in the 1900s, that shows that there was intermarriage and or miscegenation between the remnant Tribal People and other persons of various backgrounds. His father, he tells us was a mixture of European and Indian and his mother was of mixed Carib and African descent.

There are as well oral traditions collected by my father, Joseph Besson and myself. Joseph lived at Arima at Mauxica estate in the 1930s and after, and knew of the Carib community at Calvary Hill, and of the existence of several families who were of almost pure Carib descent living in Arima and its environs in the 1950s. Their relatives lived and worked on the cocoa estates on the north coast of Trinidad and were in contact, on a regular basis, with relatives in Venezuela. (This separate from the annual visits of the Warro people to Maruga). In fact, the Venezuelan connection between people with Carib ancestry and what would become an important aspect of the island’s agricultural economy in the latter part of the 19th century, the cocoa economy, is of interest to the historian. The emergence of cocoa as an important crop has a great deal to do with the lingering First People’s presence and their “Down the Main” connections.

Cocoa is indigenous to the new World and had always been cultivated in Spanish Trinidad. But around 1850 it was quite insignificant as an export crop. Its take off into a period of rapid expansion can be dated to around 1870 .

As Dr. Brereton tells us in The Book of Trinidad, “ As eating chocolate, and cocoa as a beverage became items of mass consumption in the industrilised countries; demand for cocoa in Europe and North America expanded tremendously, and this was the most important single reason for the expansion of cocoa in Trinidad.” The opening up of Crown Lands facilitated this, but it was the people, the mixture of Carib and other races, who would become known as Cocoa Panoles, who would be the actual pioneers of this important addition to the local economy of the time. The most common method employed by a great many planters, most of them in this period were French Creoles, was to get a grant of Crown lands and to allow a Cocoa Panole farming family with experience of cultivating cocoa, often with Venezuelan connections, where the crop was grown, to start cultivating it in the high woods. The clearing of the forest in such a manner that the correct mixture shade and light, moisture and protection from the vagaries of the weather, would over a period of some six to eight years, form the core of what would become a cocoa estate. This was the job that was given to this group. In such a manner communities were formed around the estates in the valleys of the northern range, central and deep south which would eventually become villages. The demand for the high quality bean grown in Trinidad would remain high. Exports had averaged around eight million lbs. a year in 1871-80 ; by the decade 1911-20 they averaged fifty-six million lbs per annum, a seven fold increase. The return of the original natives to Trinidad, now more or less mixed with other races, Hispanised, that is Christian and Spanish speaking, would become an important element of the overall population. They would revive the Spanish / Carib traditions in festivals such as parang at Christmas and breath a new life into the Santa Rosa celebrations at Arima. But most importantly they would stay close to the land and not forget from whence they sprung.

The Antique Saints of Trinidad

|

| Our Lady of Montserrat (Cambridge - Paria Archives) |

This little wooden figure of the Blessed Virgin Mary, known as the ‘Black Virgin’, is said to be a copy of a statue of Our Lady in a shrine in Montserrat, Spain.

“In Tortuga, the ‘Black Virgin’ is placed in a side chapel reserved for its veneration,” writes Sister Marie Therese in her excellent book Parish Beat. “People come from all parts of Trinidad to pray at her feet, beseeching favours. At a date close to September 8th, her feast is celebrated. No one knows, really, when the little wooden figure of the ‘Black Virgin of Montserrat’ was brought to Tortuga, but it is presumed that it came through a Capuchin missionary from Spain.”

It is interesting to note that the earliest missionaries, the Catalan Capuchin priests, first arrived in 1687. The last Aragon Capuchin came in 1758. This serves to give an idea of the age of the ‘Black Virgin of Montserrat’.

Another remarkable figure of veneration is that of La Divina Pastora at Siparia. Sister Marie Therese relates in her “Parish Beat”: “Siparia was one of the missions of the Spanish Capuchins who came from the Santa Maria province of Aragon in 1756–1758. Devotion to the divine shepherdess is centuries old, originating in Spain. It is said that in 1703 Our Lady appeared to a Capuchin known as the Venerable Isidore. In this visitation he was instructed to spread devotion to her under the title of ‘Our Lady, Mother of the Good Shepherd’. This devotion was introduced in Venezuela in 1715 and the first church was built in her honour in an Amerindian mission.”

The date of when the devotion to her was introduced to Trinidad is not known. There is, however, a parish record that states that the statue of La Divina Pastora was brought from Venezuela to Siparia by a Spanish priest, who said that the statue had saved his life. This record dates from 1871.

The statue may well be over 100 years older than that date. Perhaps it had travelled from Spain to Venezuela in 1715, perhaps it had been taken into safekeeping by the priest in those turbulent years of Venezuela’s past revolutionary period, when much of the church property was destroyed in the wars.

Santa Rosa de Lima was canonised in 1671. She was born in Peru of Spanish parents and became a nun in the Dominican order. She devoted her life to the sick and the destitute, and is remembered even today by the tribal people of the high Andes.

|

| La Divina Pastora (Cambridge - Paria Archives) |

Dating from an early period, a figure said to be that of the saint was brought to the church. It had been discovered by villagers in the high woods, and has been the focus of veneration ever since.

Sister Marie Therese records the words of Fr. Thomas:

“In 1813, the youthful [Governor of Trinidad] Sir Ralph Woodford attended the Santa Rosa festival. On this joyous occasion, the church is decorated. During the service, a cannon was discharged at intervals. At the end of the mass, ceremonial dances were performed in the church to the accompaniment of the cuatro and the chac-chac. The four leading Caribs of the mission bore the statue in procession, immediately followed by the Carib queen, who was dressed like a bird of paradise.”

According to L.A.A. de Verteuil (“Trinidad”), the king and the queen of the Caribs in the early 19th century were usually young people. The church was elaborately decorated with produce, and people came from afar to view the ceremonies.

|

| Map of Missions in Trinidad (from "Parish Beat" by Sr. Marie Therese) |