Conquerabia

|

| Photo: Kurt Jessurun/www.tropilab.com |

Legend has it that a great battle took place in ancient times in or near where Port-of-Spain now stands. The fight was between two rival tribes of Arawaks.

James Stark in a guide book to Trinidad, 1899, records that present Woodford Square was once called “Place des Ames” or place of souls by some, or “Place des Armes” place of arms by others, in commemoration of the battle.

The memory of Trinidad & Tobago’s First People lies as lightly on our consciousness as this morning’s mist in the folds of Mon Repos. Their history, long forgotten, as a book, is closed, but it is not altogether lost.

Their words, now become place names, are as huge petroglyphs that read Tarcarigua, Tunapuna, Caroni, Guanapo, Tamana, and so many others. These are scattered across our landscape and stand as markers, like mileposts from another time, marking places where they lived and died.

Then there are the remnant First People themselves, embedded in families, some still close to the land, who have managed, through many generations to maintain a sense of identity, a belief in belonging to a community of the spirit, the spirit of the ancestor.

Folklorist Mito Sampson captured a fascinating memory of the First People, perhaps the last recorded – that reached back into the 1830s or 40s, in his study of the Jamette culture of East Port-of-Spain during the 1930s and 40s, which was published in the Caribbean Quarterly’s special Carnival edition of 1957. Mito Sampson was able to tap into a rich vein of oral history that had been maintained and passed on as tribal history embroidered into the fabulousness of myth.

And what is myth? One source simple states that myth is a traditional story consisting of events that are ostensibly historical, though often supernatural, exploring the origins of a cultural practice or natural phenomenon.

In writing this article, which is in commemoration of Trinidad & Tobago’s First People being recognised, officially, as a component element, in fact the foundation member of the national community, I have chosen, in the first instance, Mito Sampson’s paper as a start in the capturing

of their oral tradition.

|

| Conquerabia which became Marine Square, now Independence Square Port-of-Spain in the 1920s. |

It was during this period that characters such as Jo-Jo, Ofuba the Slave and Thunderstone as well as personalities like Cariso Jane and Surisima the Carib would have made up the town’s Jamette society.

It is from this source, which is the crucible, so to speak, of the Creole culture that gave us Calypso, Carnival and the Steelband from which Mito Sampson drew his information. The Jamette society of the town were those who lived beyond the diameter of the inner circle of polite society, they were notorious for being absurdly scandalous, vulgar and in a way amusingly obscene.

|

| The Raconteur from Ruby Finlayson’s 1900s collection of Port-of-Spain personalities. |

Words spoken, a story is told, as a gift given. It is a legacy to pass on, a precious thing that had been handed down through what? two hundred years, since the time of the Spanish rule, in this remnant community. It was like a fossil to the eager young researcher with the notebook. Mito Sampson’s informant called himself Jo-Jo. He may be placed in history as being born, perhaps in Port-of-Spain in the 1830s or 40s.

Sampson records that “Jo-Jo was a son or nephew of Thunderstone, Chantwell to the Congo Jackos band, who lost his wife Cariso Jane to Surisima the Carib. Jo Jo became a jamette in his early twenties, and later a wayside preacher. At times he was reluctant to give the salacious details, but would yield under pressure, though he thought it was a waste of time to probe into what was best forgotten. He was strong on African slave legend, and gave me calypsoes from Ofuba the Slave and his son Possum.

“If it were not for Jo Jo, the information concerning Surisima the Carib and the legends and folk traditions of the Caribs would have been lost; Jo-Jo’s father knew Surisima personally, and had taken part in the ceremony known as “the burning of Caziria”. Jo Jo was over 92 when he died.

“According to the legends passed on by Surisima the Carib, a well known Calypso singer of the mid nineteenth century, the word Cariso, by which the term Calypso was known, prior to the 1890s, is descended from the Carib term “Carieto”, meaning a joyous song. Surisima was famous also as a folklorist and raconteur. People would pay him to come to their homes and enlighten them on long forgotten events. He was a wayside historian, and wherever he spoke, people gathered. Surisima recreated much of the old Carib tradition, which is still remembered today.

Carietos, the joyous songs of the First People, were used to heal the sick, to embolden the warrior and to seduce the fair. It is said that under the great Cacique Guamatumare, singers of Carieto were rewarded with special gifts of land, and that next to the tribal leaders they also owned the love of the fairest ladies.

In the time of the Cacique Guancangari, the two great singers were Dioarima, tall, powerful and extremely handsome, and, an undersized weakling. Their voices were capable of arousing cowards, invigorating the jaded and placating the delirious. Dioarima had two beautiful daughters who were guarded night and day. One night a singer hid in the bushes, and sang a series of haunting songs which had the two girls uneasy. The following night they escaped from their guards, and met the singer in the woods. He took them to Conquerabia (now Port-of-Spain) and lived with them in regal splendour until he was killed in battle. Guandori, a great stick-man of the 1860s, was the last of their descendants.

When the Spaniards heard of these miracle singers, whose voices spurred men on to battle even in the face of fearful odds, they used bribery and clever manipulation, and finally ambushed the two through the treachery of the Carib slave-woman Caziria. The singers were subjected to unspeakable tortures and molten lead was poured down their throats.

With the death of Casaripo and Dioarima, the Carib forces rapidly disintegrated, and were eventually conquered by the Spaniards. Surisima himself used to organise a procession of Carib descendants from the city of Port-of-Spain to the heights of El Chiquerro where a huge effigy of Caziria, the betrayer, was belabored and burnt after drinking, feasting and singing obscene songs. The only song remembered is:

‘Cazi, Cazi, Cazi, Caziria

Dende, dende. dende dariba’.

In 1859, Mr. William Moore, an American ornithologist, came to Trinidad. He gave a lecture on birds and he had cause to make allusion to the Cariso, saying that many of the Carisos are localised versions of American and English ballads. When Surisima the Carib heard that he was annoyed. Two days later he went to Mr. Moore’s hotel with a crowd of followers and he lampooned him viciously. The lampoon is preserved to this day. This is what he sung: ‘Surisima: Moore the monkey from America! Crowd: Tell me wha you know about we cariso!” They kept on singing like that creating a furor until the police intervened.”

Thanks to Mito Sampson the authentic voice of folk tradition was passed on, carrying with it the traces of a mythology that speaks of the inner memories of a people, of beauty, love and betrayal; of revenge, and of the celebration, in a forgotten ritual, of the memory of a time when our country was young.

The Land of the Hummingbird

Perhaps the oldest recorded anecdotes of the First People are to be found in Edward Lanza Joseph’s History of Trinidad, 1838. In an ethnographic study it mentions an enduring Creation Myth, how the wrath of the great spirit of Trinidad, who in defense of the beauty of the hummingbird, caused the destruction of an invader and the creation of the Pitch Lake at La Brea.

Joseph writes in his description of the flora and fauna of the island, “I now come to the smallest, but to me the most interesting of the feathered tribe, called hummingbirds, because we have here such a number of species, such endless varieties of these graceful and resplendent creatures as to justify the aboriginal Indian name of Trinidad, viz. Iere, that is to say, Land of the Hummingbird.

“The aborigines treated these darlings of nature with religious veneration, calling them beams of the sun, and supposing them animated by the souls of the happy...

“Formerly (say the Indians) the spot on which stands the Pitch Lagoon was occupied by a tribe of Chaimas, who build their ajoupas (huts) here, because the land abounded in pineapples, and the coast in oysters and other shell fish; the finest turtle and fish were here taken, and its limpid springs were frequented by countless flocks of flamingos, horned screamers, pauies (wild turkeys), blue ramiers and humming-birds.

The inhabitants of this Chaima encampment, by wantonly destroying the humming-birds, which were animated by the souls of their deceased relations, offended ‘the Good Spirit’ who, to avenge their impiety, made one night the whole encampment sink beneath the earth with all its sacrilegious inhabitants; the next morning nothing was perceived of the Chaima’s village, but instead the Lagoon of Asphaltum appeared.”

It was out of this myth, traditionally narrated by a person called Mr. Trinidado, that emerged the notion that Trinidad is the Land of the Hummingbird.

|

| Sketches of Amerindian Tribes 1841–1843 by Edward Goodall. |

The hummingbird became their object of game. The tiny creature was used by the newcomers for decoration—their iridescent feathers in startling blue, magenta, aquamarine, turquoise, yellow, green, and other shades no longer in existence, were turned in to hats and capes, wallets and walking sticks.

It is reported on the best authority that the Great Spirit of Trinidad, the “Land of the Hummingbird”, Iere, arose from his millennium slumber and moved. This move swallowed up the newcomers, plunging them into his very bowels, only to be regurgitated as a lake of steaming pitch. The First People have a story that after dying, the souls of the children of Iere return as hummingbirds, perhaps giving rise to the fable that this island is the Land of the Hummingbird.”

Two hummingbirds appear in chief on the coat of arms of Trinidad & Tobago and are prominent on the insignia of the Trinidad & Tobago Police Service and the defense forces of Trinidad & Tobago. They, as institutions of the state, protect us, the hummingbirds, as the great spirit of the island once did.

Two hummingbirds appear in chief on the coat of arms of Trinidad & Tobago and are prominent on the insignia of the Trinidad & Tobago Police Service and the defense forces of Trinidad & Tobago. They, as institutions of the state, protect us, the hummingbirds, as the great spirit of the island once did. |

| Moriche palms at Waller Field, Trinidad. |

German naturalist and traveler Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859), from a more scientific point of view, observed that the palm, called the “tree of life” by the tribal people, did in fact possess many life-sustaining qualities. The bark, for instance, contains a sago-like flour that may be used in various forms of cooking. The fruit is not only edible, but could be made, when fermented, into various sorts of drinks, some alcoholic, a sort of wine. From the large fan-shaped leaves a thin, ribbon-like pellicle is taken and rolled on the thigh or chest into a string.

From these strings, in some instances dyed into brilliant colours, hammocks were woven.

|

| An Amerindian photographed in the 1890s quite likely in Guyana for the travel book, “Stark’s Guide and History of Trinidad.” |

A creation myth (or cosmogonic myth) is a symbolic narrative of how the world began and how people first came to inhabit it. While in popular usage the term myth often refers to false or fanciful stories, formally, it does not imply falsehood. Cultures generally regard their creation myths as true (the Bible, for instance). In the society in which it is told, a creation myth is usually regarded as conveying profound truths, metaphorically, symbolically and sometimes in a historical or literal sense. They are commonly, although not always, considered cosmogonical myths – that is, they describe the ordering of the cosmos from a state of chaos or amorphousness. (Source: Wikipedia.)

The Tribal People of Trinidad & Tobago

|

| Fruit of the Moriche Palm. Herbarium , UWI |

“The larger islands, that is to say, Haiti (St. Domingo), Cuba, Jamaica, Bariguen (Porto Rico), and Iere (Trinidad) – Cuba, Haiti and Jamaica retained their Indian names – were inhabited by less ferocious tribes. Perhaps, as it has been conjectured, the Caribes easily made themselves masters of the smaller islands by exterminating the male inhabitants, but could not obtain the mastery over the larger ones. This cannot be ascertained at present; but that the Caribes had no footing in Trinidad, may be learned from Las Casas. I am aware that the learned Humboldt is of the opinion that the tribe called Jaoi of Trinidad were a section of the Caribe family; yet I am rather inclined to follow older authorities and traditions, because it appears that such enmity existed between the Caribes and other races, that they never could have resided in the same island.”

|

| A lithograph of Mount Tamana by M.J. Cazabon where according to the First People the world was began anew after the great flood. |

|

| A romantic view of life in the high woods. Hahn 1983 |

|

| Sketches of Amerindian Tribes 1841–1843 by Edward Goodall. |

“Of the Arawaaks, and inhabitants of the larger islands generally,” E.L. Joseph continues, “ the friends and companions of Columbus give us a rather favourable report (vide P. Martye, Oviedo, Herrera, Las Casas, and Ferdinand Columbus). They were as fully advanced towards civilization as were the in habitants of the South Sea Islands during the time of Cook. They built commodious dwellings, manufactured vessels of clay, equal, according to Las Casas, to the best made in Spain; they had the art of spinning cotton into cloth, and were by no means destitute of agriculture ; they made canoes of surprising capacity; they made cordage and hammocks from fibers of the coco palm and other trees. Most of those who describe them during the first thirty years of the discovery of these islands, speak highly of their mode of life, domestic economy, and general benevolence; but we should not allow the exaggerations of the early travelers to deceive us; for after a long and to them dangerous voyage, they were apt to colour too lightly the joys of the savage state they beheld. That possessed the art of weaving cotton into cloth, of dying the same beautifully, cannot be denied; but in general they went in a state of very near to nudity– the chiefs wearing only a short tunic, the rest merely a guayacco ; and according to Bartholomy Columbus, his father found the women of this island in ‘statu naturali’.

“Their diversions consisted of public and private dances ; the first was a kind of warlike amusement. Herrera says that 50,000 men and women used through the night to dance together, keeping time with wonderful precision; they accompanied them with historical songs; these entertainments were called ‘Arietoes’. “

(Note that in Mito Sampson’s account the word used by the Tribal People for joyous songs was “Carieto”).

| |

| An Amerindian burial photographed in the 1890s quite likely in Guyana for the travel book, “Stark’s Guide and History of Trinidad.” |

“The rest of their diversions consisted of a game of ball played between two parties, called ‘Bato’. According to Oviedo, they displayed surprising agility in this game, frequently repelling the ball with the head, elbow, or foot.

“Their agricultural instruments consisted of a long picket of hard wood and a kind of rude spade of the same material, with these they cultivate manioc and maize.

“Their warlike implements consisted of a bow and arrow, the latter often dipped in poison of remarkable acuteness, Sometimes they used pieces of cotton at the end of their arrows; these were saturated with inflammable resinous matter, and when fired, served to burn their enemies’ village. By way of defensive armour, they had wooden shields–the shields, I believe, were peculiar to the Indians of Trinidad.

“Their governance was absolute. Their chief was called a Cacique: his dignity was hereditary, but did not descend from father to son, but the eldest child of the Cacique’s sister succeeded to his uncle state.”

“After his famous 1492 voyage of discovery, Christopher Columbus was commissioned to return a second time, which he did with a large-scale colonization effort which departed from Spain in 1493. Although the second journey had many problems, it was considered successful because a settlement was founded: it would eventually become Santo Domingo, capital of the present-day Dominican Republic. Columbus served as governor during his stay in the islands.

The settlement needed supplies, however, so Columbus returned to Spain in 1496.”

Historian and professor of literature Christopher W. Minster goes to tell us; “Columbus reported to the Spanish crown upon his return from the New World. He was dismayed to learn that his patrons, Ferdinand and Isabella, would not allow the taking of slaves in the newly discovered lands. As he had found little gold or precious commodities for which to trade, he had been counting on selling native slaves to make his voyages lucrative. The King and Queen of Spain allowed Columbus to organize a third trip to the New World with the goal of resupplying the colonists and continuing the search for a new trade route to the Orient.

|

Sketches of Amerindian Tribes 1841–1843 by Edward Goodall.

|

“Columbus and his men spent several days battling heat and thirst with no wind to propel their ships. After a while, the wind returned and they were able to continue. Columbus veered to the north, because the ships were low on water and he wanted to resupply in the familiar Caribbean. On July 31, they sighted an island, which Columbus named Trinidad. They were able to resupply there and continue exploring.

“For the first two weeks of August 1498, Columbus and his small fleet explored the Gulf of Paria, which separates Trinidad from mainland South America. In the process of this exploration, they discovered the Island of Margarita as well as several smaller islands. They also discovered the mouth of the Orinoco River. Such a mighty freshwater river could only be found on a continent, not an island, and the increasingly religious Columbus concluded that he had found the site of the Garden of Eden. Columbus fell ill around this time, and ordered the fleet to head to Hispaniola, which they reached on August 19.”

Christopher Columbus writes into his Ship’s Log:

(Discovery of Trinidad by Christopher Columbus 1498. Selected letters of Christopher Columbus by R.H. Major 1870, Hakluyt Society.)

At the end of seventeen days, during which Our Lord gave a propitious wind, we saw land at noon of Tuesday the 31st of July. This I had expected on Monday before and held that route up to this point ; but as the sun’s strength increased and our supply of water was falling, I resolved to make for the Caribee Islands and set sail in that direction ; when by the mercy of God which he has always extended to me, one of our sailors went up to the main-top and saw to the westward a range of mountains. Upon this we repeated the “Salce Regina” and other prays and all of us gave thanks to Our Lord.

“I then gave up our northward course and put in for land; at the hour of complines we reached a cape which called Cape Galera, having already given to the island the name of Trinidad, and here we found a harbour which would have been excellent but there was no good anchorage. We saw houses and people on the spot and the country round was very beautiful and as fresh and green as the gardens of Valencia in the month of march.”

|

| The three ships of Christopher Columbus appear per chevron on the coat of arms of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago. |

Douglas Archibald in his historical account of Tobago, “Melancholy Isle”, tells us, “Christopher Columbus, during his third voyage of discovery, sighted the island of Kairi on the31st of July 1498, and he named it Trinidad. Several days later, on the 13th August,Columbus sailed away from the gulf of Paria and Trinidad, through the Grand Boca on a course that was east and north. Some time on that day, before changing that course for a westerly one, he sighted an island to the east and another one to the north : and he gave to the former the name of Assumption, while he called the latter Conception. Those are the islands that now know as Tobago and Grenada.

“In the early part of the 16th century, the explorers and adventurers who followed in the wake of Columbus, such as Ojeda,Vespucci and Juan de las Cosa, would refer to Tobago, on their charts, as Madalena, while they gave to Grenada the name Mayo.”

Over the following decades Dutch cartographers would increasingly use the word Tovaco or Tobago, said to be the name used for the implement in which a herb called cohiba was smoked for this island.

The imagination of the age of Christopher Columbus was characterised by biblical geography, alchemical science and kabbalistic thought. These located the navel of the world in Jerusalem. This island, which Columbus called Trinidad, was in the minds of some a fictional place, a legendary place in the imagination of the Old World, a place of magical monsters: home Leviathan, the great denizen of the deep, where in its Gulf of Paria they did disport themselves.

The Admiral of the Ocean Sea came upon this island in 1498, he tasted the waters in its Gulf of Paria and found them sweet and possessed of the mammalian redolence of the Leviathan. “I have found Mar Dulce,” he wrote into the log of his flag ship, the Santa Maria de la Gorda, “the sweet sea, where the fresh water battles with the salt.”

The Republic (ca. 370-360 BC) by Plato - One of the earliest conceptions of a utopia. Ptolemy had written of the “Fortunate Isles”, Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book Utopia, described a fictional island society in the south Atlantic Ocean off the coast of South America.

Christopher Colmbus named the ingress to, and egress from, the Gulf of Paria, with kabbalistic terminology Boca del Serpiente and Bocas del Dragon. The great expanse itself; Golfo de Ballina. He had seen them, Leviathan. The great whales, they formed his escort as he entered the gulf through the channel to the south as he sailed the furthest perimeter of the circumference of the world.

|

| Sketches of Amerindian Tribes 1841–1843 by Edward Goodall. |

|

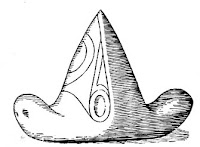

| A zemi, from Daniel’s “West Indian History”. |

To the Taíno, zemí was/is an abstract symbol, a concept imbued with the power to alter circumstances and social relations. Zemis are rooted in ancestor worship, and although they are not always physical objects, those that have a concrete existence have a multitude of forms.

The simplest and earliest recognized zemis were roughly carved objects in the form of an isoceles triangle (“three-pointed zemis”); but zemis can also be quite elaborate, highly detailed human or animal effigies embroidered from cotton or carved from sacred wood.” E.L. Joseph writes that the tribal people believed in a plurality of gods– “the chief of them they called Jocahuna.”

He goes on to source Laet who said that the island of Trinidad was possessed by two parties of Indians: one called Cunucaras, under a chief called Buchumar ; the other called Chacumries, who obeyed a cacique named Maruane. In Daniel’s West Indian Histories we learn that when Antonio de Sedeno, the Treasurer of Porto Rico, was granted Trinidad and attempted to establish a settlement in 1530, some thirty two years after Columbus, the island was described as being divided into two provinces– that of the Chacomares, under a cacique called Maruana, in the south, and that of Camucuraos, under Baucunar, in the north. The southern people were mild and friendly; and as Chacomer in an Amerindian language means “sweet potato people”, it has been suggested that they were thus called in derision by the fierce Camucuraos, who repeatedly attacked the Spaniards and endevoured to drive them out. Later writers refer to the constant feuds between the two waring tribes in Trinidad, and frequent reference is made to the warlike Nepoyo chieftain Hyarima, whose village was where Arima now stands. He it was who assisted the Dutch in their attack on St. Joseph in 1637.

Nearly a century after the discovery, and in spite of the ravages caused by the Spanish privateers and the wars of the Conquistadores, Sir Walter Raleigh, during his short stay, found the Napoios, Aruacs, Salives, Yaios, Chaimas and Carinepagotos.

“The Tamanaques occupied the centre of the island. There is a small mesa or tepuy there of that name, the English term for which is tableland or table-top mountain. The word tepui means “house of the gods” in the native tongue of the Tribal People. These tend to be found as isolated entities rather than in connected ranges, which makes them the host of a unique array of endemic plant and animal species. They are found in the Guiana Highlands of South America, especially in Venezuela and western Guyana, and in Trinidad. In Trinidad these may also be also seen at Naparima and at Montserrat in a smaller form. They mirror the most outstanding tepuis on the mainland. These great table-top mountains are the Neblina, Autana, Auyantepui and Mount Roraima. Auyantepui is the source of Angel Falls, the world’s tallest waterfall.”

Borde wrote in the 1850s-60s that “the Quaquas, according to Humboldt, crossed over to the continent with their neighbours the Salives.” He mentions “the Chaguanes, whose name a quarter of the western coast bears; the Pariagotos, a few of whom still exist; and the Cumanagotos, who lived on the eastern coast, since we find there a bay of that name. We arrived at a total of eleven tribes as above mentioned.

“When we remember that Sir Walter Raleigh only explored the south and west coasts of the island, it is reasonable to suppose that this number falls short of fact, and could be increased. The island must have been then well populated at the time of the discovery. Its population must have been at least 10,000 souls; it was divided into a great number of villages, situated chiefly along the coasts and rivers. Although these different tribes have their own dialects, it seems that Carib was the dominant language in the country; it was spoken in the greater part of Guiana, along the northern coast of the South American continent, in the lower Orinoco and in the Lesser Antilles. It stood in the same relation as Italian does to the Latin languages, being distinguished from the other American dialects by the sparkle and great variety of its sounds; it is easily recognised by the frequent occurrence of vowels and of the syllable ‘car’. A great number of the Indian names which have been handed down to us like: Guaracara, Chacachacare, Tacarigua, Caroni, etc., bear this Carib characteristic.

“All the American dialects being closely allied, it is said that the Aruaca, Chaima, Salive, Quaqua experienced no difficulty in adding to the knowledge of the language of his childhood, that of the common language of the country. It was thus in old Europe, where for a long time a great centralisation and combination of nations took place, it often happened that the language spoken in infancy was not that spoken at a more advanced age.”

No comments:

Post a Comment