|

| St. James Barracks in the 1850s. M.J. Cazabon |

The Trinidad & Tobago Police Service is the oldest public institution in Trinidad & Tobago.

|

| The Spanish presence in Trinidad was to last from 1498 to 1797 |

Its origins date from the time of the third Spanish Governor of Trinidad, the conquistador, Don Antonio de Berrio y Oruña (1592-1597), who founded San José de Oruña, the first capital of Trinidad. He appointed Senor Josef Nunez Brito to the office of Alguacil Mayor, he was the first Chief of Police. This was a very long time ago: this was when Sir Walter Raleigh visited the Pitch Lake, 1592 was the birth year of Shah Jahan, the 5th Mughal Emperor of India, famous for the building of the Taj Mahal, and when Queen Elizabeth I reigned in England.

The Police Service has served faithfully three countries and three governments: the Spanish, the British and that of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago. It has functioned under The Spanish Colonial Code, called The Laws of the Indies, whose various codes were the laws of Trinidad up to 1849, under British Martial Law during the British military administrations of Colonel Picton and Generals Hislop and Munro, 1797–1813,

|

| The Spanish fleet on fire, blockaded by the British Fleet in Chaguaramas Bay in 1797. |

For the majority of the Spanish period, 1492 – 1797, Trinidad was a virtual desert island, in that it was slowly depopulated of its original native inhabitants while never actually developed by its coloniser, Spain.

Tobago during this period, the late 16th century to the beginning of the 19th century, was an often fought-over territory that was controlled by local militias and troops stationed there to protect the property and interest of the various European governments who, at one time or the other, controlled the island.

In spite of having a very small population, Trinidad never lost its Spanish presence. There was always a Spanish governor, as it formed a part of the Vice-Royalty of New Granada. There were thirty-seven Spanish governors from 1530 to 1797. There was as well a civil administration, who were in charge of the police. This was the Illustrious Cabildo, a form of town council, in place at the island’s capital San José de Oruña and in later years in Port-of-Spain. We are told by historian Carlton Ottley that during this period there were never more than six policemen in Trinidad. The fundamental change that took place in Spanish Trinidad was the promulgation of the Cedula for Population of 1783. This saw the arrival of colonists, mostly from the French islands of the Caribbean, who introduced chattel slavery to Trinidad on an industrial scale.

Trinidad, from the start of the French Revolution of 1789 to the conquest of the island by the English in 1797, experienced a period of civil upheaval, public disorder verging on anarchy and the threat of foreign invasion.

The Spanish governors of the day, Dons Martin de Salaverria and José María Chacón, controlled just a few soldiers along with the handful of policemen under an Alguacil Mayor. Carlton Ottley tells us in his ‘A Historical Account of the Trinidad & Tobago Police Service 1592–1972,’ that to deal with violent crime and civil disorder, “. . .the Spanish Governor Don José María Chacón appointed a number of influential planters as honorary commissioners or corregidors (A corregidor was a local administrative and judicial official in Spain and in its overseas empire. They were the representatives of the royal jurisdiction over a town and its district.) As administrators of local government, these corregidors were charged with the duties of policing their respective districts, being specifically instructed ‘to take cognizance of all robberies, quarrels and disorders which may be caused, by prosecuting and apprehending vagabonds, as well as those who seduce the slaves and hid fugitives by finding work for them on their estates.’’’

|

| Brigadier General Sir Thomas Picton, governor of Trinidad 1797 – 1803 |

Military historian, Lieutenant Commander Gaylord Kelshall, in whose memory this article is writen, tells us in his captions to the Police Museum on St. Vincent Street, “When the invading British troops of Sir Ralph Abercromby departed Trinidad in 1797, they left Colonel Thomas Picton with very few regular soldiers with whom to defend the island. Picton decided on an offensive/defense strategy to hold the island against the dissident Spanish residents, Spanish troops who collected in Caracas, Cumana, Guiria and Angostura, and French Republicans who were supported by a fleet of privateers operating in the Gulf of Paria under the command of the mulatto ship’s captain Jean Bedeau.”

Because of his soldiers’ predilection to tropical diseases and rum, Picton put his few European troops into garrison and relied on black troopers seconded from Colonel Drualt’s Guadeloupe Rangers, the 9th West India Regiment, who had been fighting Victor Hugues in Guadeloupe, and from Lieutenant-Colonel Gaudin de Soter’s Royal Island Rangers, the 10th West India Regiment, to form the core of Picton’s Royal Trinidad Rangers.

| ||

Lieutenant-Colonel Gaudin de Soter “A company was raised by my son under the direction of general Abercrombie, and left to the order of general Picton, for the purpose of aiding in the preservation of tranquility in the colony”. (From de Soter’s testimony at Picton’s trial.) Gaudin de Soter was a French Royalist officer who had joined the British in the fight against French revolutionary forces in the Caribbean.

His Royal Island Rangers, later the 10th West India Regiment, comprised of Free Black and Coloured men, were placed under the command of Governor Thomas Picton by General Abercromby. This contingent became the core of what would evolve to be the Trinidad and Tobago Police Force.

Historian, Roger N. Buckley, in his ‘Early History of the West India Regiments’ tells us that “Apparently most of the first recruits for these corps were free blacks and free mulattoes. Many of the officers were French and the pay of these corps was the same as for British regiments. Among these corps were Soter’s Royal Island Rangers, which was raised in Martinique, and Drualt’s Guadeloupe Rangers.’” Thus the precedent for the recruitment of West India Regiment soldiers into the Trinidad Police Force was set.

|

| The six-pointed star was appropriated by the Trinidad Police Force and the Trinidad Militia in 1802 |

The Origins of the Marine Branch

These recruits also operated a sloop of war, the H.M.S. Barbara, as Picton’s Marine Police Force. Picton’s police, the Royal Trinidad Rangers, a composite of the above, comprised a uniformed element who patrolled the town of Port-of-Spain and paid particular attention to the waterfront, as well as a secret service, who operated in Trinidad and Venezuela. These early irregular troops, navy, and police were paid out of Picton’s private funds until 1802, when they were granted official recognition. During this period, Picton’s Royal Trinidad Rangers took to wearing, as a badge, a six-pointed star which they identified with Picton’s patron saint, St. David of Wales, as their own emblem. In 1802, the six pointed star became the official badge for both the Militia and Police, which is still used today. Shako plates and gorgets, once part of the uniform of the Militia, dating from 1802 to 1842, exist in the Military Museum in Chaguaramas.

|

| At left, a Police Constable attached to the Marine Branch. At right, Marine Branch launch comes alongside the St. Vincent Street Jetty. |

|

| The Harbourmaster's Office with Marine Branch Launches alongside. |

The police under Picton enforced British martial law supported by the Spanish Laws of the Indies with draconian effect. There were public executions, torture in the Royal Gaol, public floggings and mutilations inflicted on criminals and on those suspected of sabotage.

Brigadier General Sir Thomas Picton, as he was to become, was the founder of the modern Trinidad and Tobago Police Service. The use of the six-pointed star as a cap badge for locally commissioned officers only, was continued in the First Division until 1938-39, when under the command of Colonel Walter Angus Muller, the first Commissioner of Police, it was introduced to all ranks as a cap badge. British officers who were assigned to the Trinidad Police used the cap badge and other insignia of their regiments.

Picton’s successors, Brigadier-General Sir Thomas Hislop, 1804-1811 and Major-General William Monro, 1811-1813, imposed law and order to control the still unruly populace. Their most constant preoccupation, apart from invasion by Republican France, was the possibility of slave uprisings on the estates, as resistance, by the enslaved had been the trigger for rebellion in other islands.

This was a genuine concern, because with the abolition of the slave trade in 1807, the planters, fearing that their supply of free labour was going to end sooner rather than later, worked the chattel slaves cruelly and in many instances to death in an attempt to recoup their investment and make a profit.

|

| The Orange Grove Barracks on Charlotte Street was built in 1804; it is now the General Hospital in Port-of-Spain. |

A census published in Lionel Fraser’s ‘History of Trinidad’, taken in 1803, shows that the enslaved population stood at twenty-eight thousand men, women and children. There were six hundred and sixty-three English persons, five hundred and five Spaniards, and one thousand and ninety-three French persons. There were five hundred and ninety-nine English-speaking Free Blacks and People of Colour, one thousand seven hundred and fifty-one free Spanish persons of mixed heritage, and two thousand nine hundred and twenty-five mulattoes of French origin who were Free Blacks and People of Colour. (This was a legal definition under the Cedula for Population of 1783.)

This made up a free population of seven thousand five hundred and thirty-six, with the Free Black and People of Colour being in the majority.

|

| Sir Ralph Woodford Bart. |

With the emancipation of the enslaved throughout the British Empire in 1838 a new dispensation for the civil society of Trinidad and Tobago commenced. This necessitated the disbanding of the previous policing regime, ending the authority of the corregidors, and a reorganisation of the police establishment in the colony. On the 13th of August, 1838, an ordinance to establish a rural system of police was proclaimed. This new ordinance created new police districts, excluding Port-of-Spain. They were St. Joseph, Eastern district, Carapichaima district, Naparima district and a Southern district.

The reorganisation of the police, by the end of 1842 saw the creation of the posts of inspector, two sub-inspectors, one in Port-of-Spain and another in San Fernando, ten sergeants and seventy-two constables. There were now twelve police stations. Reflecting the society, indeed the western world at the time, that was convinced of the superiority of the Europeans, all commissioned officers were British.

| ||

The West India Regiments formed on the 24 April 1795

became an integral part of the regular British Army.

In 1856, the West India Regiment of the British army switched

its attire to a uniform modelled on that of the French Zouaves.

Recruitment for the police was a pressing problem in the 1840s. There was a reluctance in the local population to enlisting in the Force. This may have dated from Spanish times, there was, as well, the living memory of Picton’s police methods, and a lack of prestige associated with the job itself. This stemmed from the low pay that attracted ne’er-do-wells and the nature of the duties policemen were called upon to perform by the authorities. These ranged from dog and rat catcher to sanitary inspector, to turnkey, postman and fireman and a range of other duties, some of which were considered by the Creole population in general to be demeaning. Beyond that there was the problem of language: the vast majority of local men in the 1840s-70s were French Patois-speaking, while the officers were English, and quite apart from that, there was the difficulty that many locals experienced with enforced discipline. They were simply not accustomed to it. Governor Sir Henry McLeod wrote, “It has been thought that we might procure men from England or Ireland at a cheaper rate, but my experience tells me that any attempt of that kind would be unsuccessful, as, if a number of men were brought out for the purpose, more than half would be in hospital with delirium tremens within six months.”

Cheap rum and tropical diseases did take a toll on the inexperienced. In the end, several members of the Metropolitan police were brought to Trinidad, along with two constables, and eventually, as Ottley records, “more Barbadians were recruited”, the thinking being that they were mostly taller and were Protestant, they spoke and understood English, as did the British officers and Regimental Sergent Majors who drilled and trained them.”

|

| Rioting outside the forerunner of the Red House in 1849. |

|

| Police Headquarters, also referred to as the Depot, St Vincent St., Port-of-Spain, built 1876. |

|

| Irish Non-Commissioned Officers and Constables. |

The need for another “remodelling the Force” became urgent after the events of October 1849. The population had expanded to include West Indians coming from the other islands as well as people from various parts of Europe who were fleeing war and starvation, many of whom did succumb to drink and riotous behaviour. There was as well a growing and marked sense of individualism that expressed itself in an expanding community of people who lived mostly in east Port-of-Spain, who saw themselves as belonging to a parallel society, ‘a hoodlum element’, with gangs that engaged in brawls, stick fighting, cockfighting, drumming, prostitution, the creation of ribald songs, and vulgar, outrageous and at times dangerous behavior. This was the crucible of the Jamette class that would keep the carnival spirit alive, in spite of the opprobrium that was heaped upon it by polite society and express it in Cannes Brulées carnival at a later date as a form of resistance to authority. With the growing industrialisation of agriculture, an expanding railway, a prosperous commercial sector, imposing government buildings and an increasing middle-class, there was more valuable property and important persons to safeguard and protect. As a result, this period saw the Force being manned increasingly by ex-service men from the West India Regiments that had been raised in West Africa as well as men from British regiments who had been discharged in the region after their tours of duty had expired. The look of the rank and file of the Trinidad Police Force towards the end of the 19th century was multi-racial.

| ||

Inspector-General of Police

Captain Arthur Baker 1877–1889

The Ashanti type pith helmet was introduced

in 1890 to the Trinidad Constabulary.

It had become popular after the Anglo-Zulu War.

Originally made of pith with small peaks or “bills”

at the front and back, the helmet was covered

by white cloth, often with a cloth band (or puggaree)

around it, and small holes for ventilation.

Military versions often had metal insignia

on the front and could be decorated with

a brass spike or ball-shaped finial.

The chinstrap would be either leather or

brass chain, depending on the occasion.

Remarkable for its time, it was the tallest building in Trinidad and featured the novelty of a ball on the top of the flag-post which fell, to the sound of a bugle call, precisely at mid-day G.M.T.”

Lieutenant Commander Kelshall tells us that “In 1879, the Royal Commission on Defense decided that regular British troops could be withdrawn from Trinidad and replaced by a Volunteer Military force, who in the event of trouble would hold the island until the Royal Navy could arrive with reinforcements.”

“In 1889,” we learn from historian Olga Mavrogordato, “the St James Barracks, which was built in 1827, was handed over to the Trinidad Government with an understanding that, should the British Army ever wish to return, they should have it. A decision had been taken whereby a body of police were to be trained in the proper use of arms at St. James Barracks to provide protection for the colony when necessary. It is as a result of this decision that St. James Barracks became a training school for the police. In 1906, forty-two men of the Mounted Branch were transferred to St. James where they were trained in the art of horsemanship.”

|

| A detachment of police in the 1890s drawn up outside the Princes Building. |

|

| The Trinidad Artillery at practice at St James Barracks in the 1900s. |

|

| The Police Hospital. |

|

| Inspector John N. Brierley 1871 |

The reorganising, retraining and rearming of the Trinidad Constabulary as a Battalion of Light

|

| A detachment in ‘Marching Order’ kit in barracks, note mascot. |

|

| In ‘Marching Order’ kit, note Lewis machine gun at left. |

The authorities, mindful of the fears of the ‘respectable persons of all classes’ of a general uprising of the blacks, which had been inherited as a memory of slavery, now became alarmed by a section of the East Indian community who produced the Hosay festival annually. The authorities believed that there was cause for a strong, armed and disciplined force to guard against what was thought to be dangerous elements within the Indian community on the cane estates, as well as the blacks in the overall urban society.

|

| Trinidad & Tobago Constabulary on parade. |

The Port-of-Spain Gazette of October 1898 reported that “That the new military program is beginning to take shape. A new body of fifty armed police is to be added to the Police Force and to be permanently stationed at St. James’ Barracks under the command of Supt. Sergent Shelston. One of the several sergeants from the Irish Constabulary has already arrived and will replace Sergeant Shelston at the Police Station (Police Headquarters). His name is Dennis Cassidy. It appears that there is to be in future a regular interchange of men between the Police Station and the barracks, which will ensure the efficient training of the whole Force as an armed body whilst providing an ever-ready body for any military emergency.” The Police Hospital on Charlotte Street was opened in 1894. Also in that year the Fire Brigade was made a separate unit of the Force.

A report from an Inspector who was a serving Major General in the British Army stated: “Inspection of Trinidad Armed Police, December 7 and 8, 1904 Turn-out. - Very fair. The Inspector-General reported that gaiters (Army pattern) has been provided and that water-bottles were ordered. Arms. - Martini-Enfield. Long bayonet. The Inspector-General states that no change in the arms is contemplated at present, as the Colony possesses a large number of rifles of the above description. Although the Martini-Enfield rifle is in itself a very good weapon, troops armed with it are naturally at a disadvantage when opposed to others armed with a magazine rifle of any description. Drill. - Several movements in Part V, Infantry Training, were executed very creditably under the Deputy-Inspector General, Mr. Swain. Skirmishing. - A simple tactical exercise involving an attack was very intelligently carried out under Inspectors Greig and Brierly. Street Fighting. - Very practical method of blocking and patrolling streets with a section of men was illustrated - special means were taken for searching houses. Ride by Mounted Police. - 7 mounted police executed a ride very creditably. Musketry. - On the 8th I witnessed a few men firing on the range. The shooting was moderate, and I have little doubt it will improve with more practice. Barracks. - On the 10th instant I visited the headquarters. The barracks are in good order. The dormitories still are very crowded. This, however, will be remedied when the Depot is opened. Hospital. - I visited the police hospital on the 13th. It appeared to be well found and adequate in size to the requirements of the Force.”

The idea of forming a permanent body of armed men trained to handle civil disturbances was born out of the police maintaining a close scrutiny of the changing political and evolving social tensions that were unfolding in a society that was becoming increasingly conscious and restive of the limitations of crown colony rule. This body of policemen, the first Riot Squad, was brought into action on the 23rd of March 1903 for an incident known as the Water Riot, when, as historian Angelo Bissessarsingh informs us, “Governor Maloney, perhaps expecting public unrest, ordered the Inspector-General of the Trinidad and Tobago Constabulary, Colonel Hubert Brake, to have 35 armed policemen sequestered within the Red House in addition to several dozen outside. In an attempt to limit access to the Public Gallery it was proclaimed that access would only be granted by a system of allotted tickets. The Ratepayers resisted and deemed this action to be illegal and attempted to storm the Gallery at 10.30 am but were repelled by Brake and his officers.” The ensuing riot caused the Government Buildings, the Red House, where the Legislative Council was in session to catch on fire triggering the reading of the riot act resulting in the Constabulary opening fire on the crowd resulting in eighteen people being shot and killed and fifty-one wounded.

Local Commissioned officers wore the six-pointed star which had been identified with Picton's patron saint, St. David of Wales. Foreign Commissioned officers, at right, wore their Regiment badges.

Sergeant-Superintendents wore a crown on each sleeve. Cap badge bore a crown and the monogram G.R.I., George King & Emperor. Station Sergeants wore four stripes on the lower sleeve. Cap badge bore a crown and the monogram G.R.I., George, King & Emperor.

Before 1938 a crown & three stripes formed the cap badge for Sergeants. A crown with two stripes for Corporals, the regimental number for Constables and Lance-Corporals, with a crown.

The Mounted Branch would demonstrate their skill at horsemanship with gymkhanas at St. James Barracks on occasion.

The Police band in the 1890s.

The guard house at the entrance to Government House.

The winners of the police annual marksmanship competition.

The Belmont police station.

The St. Joseph police station.

|

| Government House |

Elements of the 3rd West India Regiment, the Zouaves, stationed at St. James Barracks during the riots of the late 19th century.

The foundation for discipline, the maintenance of high morale, an esprit de corps, and a military tradition that persisted for a great many years in Trinidad and Tobago’s police establishment, had its origins in the 1900s.

At St. James Barracks, Police Headquarters in Port-of-Spain and in San Fernando and in Police

|

| The Cenotaph at the Memorial Park was inaugurated on 28th June 1924. |

There were, in the ranks in the 1900s, men who had served in India with the British army and with the West India Regiments. The West India Regiments were raised in the West Indies during the French Revolution as Ranger Companies and also in Sierra Leone on the west coast of Africa. They had seen active service in the wars in the Gambia and in the Anglo-Ashanti Wars of the 1880s. Individuals had been recognised for their gallantry, receiving Britain’s highest awards. For example, Sergent Samuel Hodge V.C., of the 3rd West India Regiment, was a recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest and most prestigious award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth soldiers.

What is of significance is that the police in Trinidad were almost all, not Trinidadian-born. Its officer corps was comprised mostly of British officers, with perhaps one or two local whites; the Drill Instructors were seconded from British Regiments and the main body of men were made up of West Indians and men who had originally enlisted in West Africa in

|

| Trumpeters of the Police Band sound the Last Post for the honoured dead. Lest We Forget. |

The Memorial Park in Port of Spain honours the memory of those Trinidadians and Tobagonians who served in the armed forces of the Empire, and remembers those who fell in its defense in two world wars.

Erected in the 1920, the cenotaph (from the Greek kenotaphion: kenos, empty + taphos, tomb, a monument for people who are buried elsewhere) is topped by Nike, the winged goddess of victory, with one foot placed upon the globe. In her left hand, held high, is the victor’s wreath of laurel, in her right, an acacia branch for the honoured dead. The obelisk itself rises out of a barque, symbolizing that which takes the souls of the departed across the river Styx. In bow and stern sit the figures Pathos and Grief. Grief bends her head to look at a scroll unrolled upon her knees, and Pathos in the bow holds a funerary wreath.

Above the inscription which reads “In honour of those who served, in memory of those who fell” stands a soldier, rifle at the ready, astride a fallen, wounded comrade. The brass plaques list the names of some 170 Trinidadians and Tobagonians who died in the First and Second World Wars.

In the First World War, Trinidadians served with valour. Fifty-five silver war medals were awarded. In one engagement in Palestine’s Jordan valley, one Distinguished Service Order, two Military Crosses and one Distinguished Conduct Medal were won by members of the First Battalion. Dozens of Trinidadians distinguished themselves in the defense of freedom. To name two: Air Vice Marshall Claude Vincent, who became one of the highest-ranking officers of the Royal Air Force, and General Sir Frank Messervy, who commanded the Fourth Army Corps and the Seventh Indian Division in Burma. He received the surrender of the Japanese forces there, when General Itaguki handed over his sword and the one hundred thousand men under his command in Rangoon in 1945.

Colonel Herbert Brake assumed command in 1902, he was succeeded by Colonel George Swain in 1907. The military tradition was further enhanced with the start of the first Boer War in South Africa in 1880. This saw men from the Trinidad Constabulary volunteer for service with British regiments. Streets in Woodbrook were named by the colonial government for the British generals of the African wars who had commanded these men; Roberts, Buller, Gatacre, Kelly-Kenny, Baden-Powell, Kitchener and others.

Very much the same spirit was to prevail with the advent of the First World War that according to Carlton Ottley, “no fewer than three officers, ten non-commissioned officers and twenty-one men joined the West India Regiment.” Policemen, trained at St. James Barracks, would perform their duty with loyalty and gallantry on the battle-field, with some upon returning home rejoining the Force. They strengthened the military traditions of discipline, loyalty and duty. This also served to entrench an enduring family tradition within the Force that would pass from father to son.

This was reflected in the composition of the Force with the increase of Trinidadians serving. Ottley writes, “ . . . by 1922 the strength had grown to seven hundred and thirty-nine men, of whom four hundred and twenty-seven were Trinidadians, one hundred and twenty-three were Tobagonians and one hundred and eighty-nine were Barbadians.”

Colonel George Herbert May succeeded Colonel Swain in 1916 and was to serve as Inspector-

|

| Colonel George May,Inspector-General of Constabulary 1916-1930 |

In May’s day, the Constabulary on parade was a formidable sight and an important element in the display of imperial power. It was a demonstration of the order, discipline and loyalty of colonial forces to the crown. Carlton Ottley points out, “Daily parades were held on the compounds at Police Headquarters in Port-of-Spain and San Fernando, and regular parades of battalion drill were carried out at Shine’s Pasture, now Victoria Square, or on the Queen’s Park Savannah.” There were regular route marches through towns and across the countryside accompanied by the Police Band and demonstrations of horsemanship with gymkhanas held regularly at the St. James Barracks. Important parades such as King’s Birthday Parade, Empire Day, Memorial Day and parades for the arrival or departure of governors and visiting dignitaries were occasions that drew large admiring crowds with, at times, contingents of two hundred or more policemen on parade. Police Band concerts at the band stand in the Royal Botanical Gardens as well as at other venues, became for many years an important cultural feature in

|

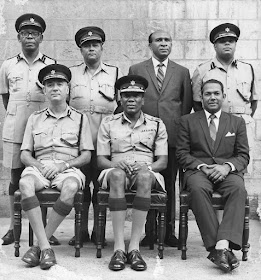

| Colonel George May, center, with officers of the First Division. Second from the left is Sub-Inspector Carr, father of Commissioner of Police “Sonny” Carr. |

There were now six police divisions throughout the country, including Tobago, each with several stations that were at all times fully manned. These stations were equipped with stables, barracks to house the men and with accommodations for officers. The starting salary in the Force was $24.00 a month. This was regarded as very good, at the time when store clerks made $5.00 or less, per fortnight.

|

| Colonel Arthur Mavrogordato Inspector-General of Constabulary and Commandant of Local Forces 1931–1938. |

Lieutenant Colonel Harragin D.S.O.

Sub-Inspector Harragin joined the Police Constabulary on 1st February, 1905. He left the colony in 1915, with the first battalion of the B.W.I. Regiment to serve in the Great War, in which he and his battalion distinguished themselves against the Turks in the charge on the Damieh Bridgehead in the Jordan Valley, Palestine. Harragin was awarded the D.S.O. as a direct result. Also seeing action with the first battalion of the B.W.I. Regiment in the Jordan valley that day was Lance-Corporal Julien, also a Policeman. He received the D.C.M. for valourious service.

The D.S.O & D.C.M are the second highest awards for gallantry in action after the Victoria Cross.

On their return to Trinidad, Lieutenant Colonel Harragin and Sergeant Julien took up their regular duties in the Trinidad & Tobago Police Force.

Lance-Corporal Julien D.C.M.

The strength of the Force in 1934 stood at about two thousand men. Contrary to popular belief, Colonel Mavrogordato did not ‘give’ the police star to the Trinidad & Tobago Police Force because he had served in Palestine, he was not Jewish and the state of Israel had not yet come into existence.The years between the World Wars, the 1920s-30s, was a time of very great poverty in Trinidad and Tobago. The failure of the world’s monetary order, known as the Great Depression, as well as the aftermath of the war had caused the markets for the island’s agricultural produce, mainly sugar and cocoa, to collapse. There was not just poverty on a very wide scale, along with the deprivations caused by the inequalities of colonial life, but many people faced actual starvation.

Militant trade unionism in Trinidad and Tobago was to grow and take root in all of the above and express itself in the canefields and in the oilbelt of Trinidad.

|

| The Reserve Platoon in 1937 under the command of Inspector Ogier. |

|

| Corporal Charles King |

|

| Sub-Inspector Bradburn |

Power took the warrant from Price, gave it to Belfon and said; ‘You read it.’ Belfon read it and Power then told him to arrest Butler.

“Butler then said to the crowd; ‘Are you going to allow them to carry me down like this?’

“The crowd replied with a resounding ‘No.’

“Bottles and stones were then pelted at the police from all sides. Power and party retreated from the fusillade of missiles, walking backwards to the vehicles. The crowd then began to throw missiles at the vehicles, some of which narrowly missed Constables Callender and Ashmead . . . Callender drew his revolver and stood in a threatening manner outside the car. Hunte and Price ran past the car, one of them was bleeding from a cut on his forehead. Liddlelow also had his revolver drawn; Power, who was unarmed, was calling on the crowd to behave themselves and instructed the police not to shoot. He then got alongside the driver, who in the meantime had

managed to get behind the wheel. Power was struck with a large stone on the left side of his head, just below the neck. He dropped to the ground like a log. Liddlelow, with help from other policemen, put Power in the car while the others climbed in the jitney. Liddlelow stood on the running board of the car with his revolver drawn and both car and jitney retreated somewhat ingloriously.”

The wound received by Major Power was to take him out of the action of the day and ultimately led

|

| Major Wilfred Power |

information concerning Corporal King. He mustered eighty policemen and left with a bus and two cars for Fyzabad junction.

“As the party of policemen proceeded on its way, several stones and bottles were thrown at them. Suddenly, a shot rang out and Bradburn, who had just walked past the car driven by Callender, cried out as he fell to the ground clutching at his chest.”

|

| The funeral of Sub-Inspector William Bradburn at the Military cemetery in St. James where the remains of Major Wilfred Power are also interred. |

|

| The grave of Detective Corporal Carl, alias ‘Charles or Charlie’ King. |

Lieutenant Commander Kelshall, who was in charge of the political prisoners detained on Nelson Island in 1970, sums up the Butler riots in his book, ‘The Great War’ thus, “Butler was the first of a long line of rebel leaders whom Trinidad idealised in preference to the men who stood for law and order. Men who created conditions of anarchy, who created the opportunity for hooligans to work their evil on innocent citizens. They themselves were seldom involved in the unlawful acts, but who by their conduct and oratory sanctioned them. Everyone remembers Butler, but few remember Corporal Charles King, or have ever heard the names Bradburn or Power.”

Uriah Butler was eventually arrested. When he was released from jail in 1939, he was welcomed back in the oilbelt with ‘warmth and adulation’, as historian Michael Anthony writes in his book ‘The Making of Port of Spain Vol 1’. As Anthony writes further:“His old and tried companion, Trade Unionist Cola Rienzi, was overjoyed. Rienzi showed his feeling at a Legislative Council meeting on June 16, 1939, during a debate on public holidays. Rienzi called on Government to declare the date of the oilfield riots a public holiday in place of Empire Day. Turning to the Attoney-General, Rienzi said:’June the 19th, Sir, is a day which in the minds of the workers marks a landmark in the history of the working class movement.’ Cipriani retorted:’All those who have the best interests of the working classes at heart would like to forget forever June 19 and are not asking for the making of a day for the adulation of false heroes.’”

This holiday was not granted until 1973.

In 1938 the nomenclature of the Force was changed from the Trinidad and Tobago Constabulary to the Trinidad and Tobago Police Force in the new Ordinance No. 5 of 1938, under which the Inspector General of Constabulary became the Commissioner of Police. New posts of Superintendent and Assistant Superintendent were created. The title Superintendent Sergeant, the ‘Super Sergeant’, gave way to Station Sergeant. Also in that year, Colonel Walter Angus Muller became the first Commissioner of Police. It was during his tenure that the emblem of the Force, the six pointed star, which was previously worn only by local gazetted officers, in remembrance of Colonel Picton’s patron saint, St. David of Wales, was allowed to all ranks as a cap badge.

|

| The Mounted Branch on parade with drawn sabres. |

The Second World War also saw policemen depart for active service overseas. No actual figures

|

| Colonel Walter Angus Muller, 1938-1948 |

This tended to generate tensions that had to be handled with discretion, as there were confrontations between police and servicemen.

|

| A police corporal wearing the police star introduced as a cap badge in 1945 for the first time for all ranks. |

The secret war: Lieutenant Commander Kelshall tells us that “Trinidad, because of its strategic location with regard to South America and the Panama Canal, both its own oil reserves and those of Venezuela, became an object of German interest before and during the Second World War. When the Gulf of Paria became a rendezvous for convoys and the significant US naval base was established, Trinidad drew a lot of attention from German submarines. To counter the German threat, the British MI 5 under Major Badenough and MI 6 under Major Wren set up their secret service headquarters at the Bretton Hall Hotel. They virtually took over the Police Special Branch, which at that time was based on Frederick Street, as their front line unit in counter espionage, the secret war. The police were also

|

| In 1943 Assistant Superintendent Arthur Johnson became the first black Gazetted Officer promoted from the ranks. |

As soon as the war in the Caribbean escalated in 1942, the secret war in the island became intense, with constant hunts for spies and double agents, many of whom were caught and shipped off to Canada for further interrogation. Trinidad was declared the international inspection port for all air and sea travel to and from South America, and Special Branch carried out searches, inspections and counter intelligence operations. On occasion, they were required to use selected applications of deadly force in this dangerous clandestine world of counter intelligence. They were assisted in some of their operations by specially selected and trained members of both the Customs Division and the Boy Scouts. Most of what the Special Branch accomplished in their numerous undercover operations must remain secret, but under the direction of MI 5 and MI 6, they played a major role in keeping South America either neutral or in the Allied camp, despite the wishes of the German-speaking South Americans and the aspirations of some of the Dictators on the continent. At the same time, they helped to cut down on the losses in the Battle of the Atlantic.

“At the start of the Second World War, the Local Forces consisted of one regular and one part-time battalion of infantry. This was inadequate to handle the defense of the island and secure the oilbelt and refineries, as well as handle marine patrol. Thus the Police Force was required as a mobile light infantry reserve, although they had ceased infantry training some time before.

|

| A detachment of police as a mobile light infantry platoon. |

Under the threat of a dramatic German naval presence in the Atlantic Ocean, for example the German battleship “Graf Spee” with its accompanying flotilla breaking out into the shipping lanes in 1939, virtually the whole Force was withdrawn from all other duties and deployed to the south coast alongside the soldiers. Their job in the cities and towns was taken over by the Special Reserve constables, the rural constables and precepted Boy Scouts. This established a working relationship that existed for the rest of the war, because when the Graf Spee crisis was over they found that the reserves had done a creditable job.

|

| A Boy Scout troop from Queen’s Royal College. |

|

| The Marine Branch on harbour patrol was trained in the use of depth charges, and in heavy machine gunnery (Source: Imperial War Museum) |

|

| Commissioner of Police, Colonel Eric Beadon, 1949–1962. |

An early innovation under Beadon’s watch was the introduction, in 1950, of the 999 emergency call number. Also in that year the colonial Government, by Ordinance No. 14, created the Trinidad and Tobago Police Service Social and Welfare Association. Carlton Ottley writes, “The new institution, dedicated to the welfare of its members, for the first time allowed policemen to have a direct say in the conditions under which they would work. In the future, as a consequence, they would not merely have to do and die. They would be free, as they are today, to decide where both the interest of the country and that of themselves and their families rest. The formation of the Association was in fact a most revolutionary turn in the affairs of the Force, one which over the years has produced inestimable benefits both to police and public.” This was, as we shall see, not the view of the officers who led the Force.

|

| Colonel Eric Beadon, centre, on his left, Assistant Superintendent Clive Sealy, with Superintendents, Inspectors, Sergeants and men who made up the Depot (Headquarters) company. |

This period also saw the creation of the canine division with the introduction of four Alsatian dogs to help in the detection of crime. The mid-fifties witnessed the introduction of a new aspect of the Force, the policewoman. This was seen as such a novelty that calypsos were composed, the singer wanting the policewoman to not just arrest him, but to hold him ‘tight, tight, tight.’

|

| Commissioner of Police Colonel Eric Beadon presenting ‘Best Stick” to a W.P.C. The first Women Police Squad was commissioned in 1955. |

illegal immigrants, particularly from the other islands, have become such a scourge that the calypsonians have made many a song about.

|

| Governor-General Sir Solomon Hochoy inspects the Guard of Honour at the opening of Parliament in the late 1950s in company with Senior Superintendent Dennis Ramdwar. |

|

| She inspects a guard of honour drawn up by the Police Force and the West India Regiment. |

|

| The band of the West India Regiment on parade in Port-of-Spain. |

|

| Sir Joseph Mathieu Perez, Kt., Q.C., LL.B., Chief Justice, inspects the Guard of Honour drawn up outside of the Red House at the Opening of the law term in the mid-1950s. |

A fresh political climate was inaugurated in 1956 by Dr. Eric Williams with the formation of the People’s National Movement. Ottley tells us that 1959, under Colonel Beadon, who served as Commissioner from 1949 to 1962, the Special Branch was created. This was also a time when several local men were gazetted to replace returning expatriate officers. When asked, by the head of a Commonwealth Commission inspecting the Police Force in 1964, about East Indians entering the Force, Commissioner of Police G.T. Carr responded that the selection board had been trying everything possible to increase the number of East Indians in the Force, because he was of the opinion that the Force should be the representative of the population. (Daily Mirror, 1964)

|

| The First Division dining at Police Headquarters in 1968. Assistant Commissioner Eustace Bernard is at the head of his table. |

The political atmosphere, in the lead-up to Independence, proved to be divisive on many levels. The most obvious differences were racial, as tensions grew not just between the two largest racial segments in the country, that represented the political divide, the Africans and the Indians, but overtly, and for the first time, between the blacks and the whites.

|

| Commissioner of Police, George “Sonny” Carr, 1962–1966 |

It would appear that they were expected to give up that role at Independence with the creation of a Defense Force. In 1961 there were public misgivings voiced in the press concerning any changes, with particular regard to placing the Police Force under ministerial (political) control. In the year after that, 1962, the appointment, dismissal and promotion of members of the Force were taken out of the hands of the Commissioner of Police with the setting up of a new Police Service Commission that would take over all responsibility for the recruitment, promotion, discipline and retirement of members of the Police Force. During his time as Commissioner, Trinidad and Tobago was host to the visit of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II and his Royal Highness Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh. This state visit lasted from February 7th to the 10th. In April of that year the country played host to His Imperial Majesty, Haile Selassie. These state occasions necessitated police work on several levels, from ceremonial parades, to the actual organising of events, to security, to crowd control. Assistant Commissioner Eustace Bernard was in charge of the organising and implementation of these state occasions.

|

| Her Majesty enters the Red House to open to open Parliament. She is accompanied by the Speaker of the House and the President of the Senate. |

|

| A woman police corporal (left) in the new uniform issued for W.P.C.’s in 1965. |

|

| H.R.H. The Duke of Edinborough, Prime Minister Dr. Eric Williams are saluted by Col. Geoff Serrette and Commissioner of Police Sunny Carr (1965) |

|

| A Police Guard of Honour drawn up outside of the Red House on the occasion of a visit of His Imperial Majesty, the Emperor, Haile Selassie, Emperor of Ethiopia in 1965. |

|

| Prime Minister Dr. Eric Williams as a guest of Commissioner of Police “Sonny” Carr at the Commissioner’s residence at St. James Barracks. |

As Kelshall was to remark in his book, ‘A Close Run Thing’, “What everyone (in government) overlooked, either deliberately or simply because no one in the hierarchy realised it, was that from the end of the Second World War to the week before Independence, the Police Force had been the army, and that they had a tradition of being the army for more than a century.

It was unrealistic to ask the police to overnight become a civil organisation.

In a token gesture, the name Police Force was changed to Police Service (in 1966) and they were now supposed to be a civil organisation.” In actual fact, the standing orders remained fundamentally in place as were the men who commanded the Police Force.

The year of our Independence, 1962, also saw Dr. Eric Williams become the first Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago. Independence marked the end of an era in the affairs of the Trinidad and Tobago Police Force. They were no longer responsible to the British Government, but to the people of Trinidad and Tobago. In Kelshall’s opinion, Dr. Williams was “an autocratic leader and as such he must take much responsibility for what took place immediately after Independence.” Kelshall believed that Williams started with a serious disadvantage. “He was a social historian. . . he knew very little of military affairs. . . The fact that he annually laid a wreath at the Cenotaph where there were one hundred and eighty names inscribed never seemed to reach him. Unfortunately, his influence was so strong that his view of military affairs was widely copied and contributed in no small measure to the lack of a military tradition in Trinidad and Tobago in the post-war years.

“He was put out by the British insistence that to become independent Trinidad and Tobago would have to have a military force. He did not want the Trinidad and Tobago Regiment that was fostered on him.”

This was a time of fundamental changes affecting not only the institutions of the state but the entire society, as adjustments were made psychologically and materially to the Independence of Trinidad and Tobago from Great Britain. One such change was the nature of the Press and its relationship with the police. At the 1964 Commonwealth Commission of inquiry into the Trinidad and Tobago Police Force. Commissioner Carr stated “The main reason that our efforts have not been very successful, regrettably is a most important medium for promoting public relations, the Press, is by no means co-operative.” He charged the newsmen with misconstruing, distorting and fabricating news and said it has had adverse effect on the Force. He said that news that would give the Force credit was seldom given prominence.

The decades of the 1960s–70s, in the world over, was a time of social upheaval and revolutionary changes, caused in part by the coming of age of a generation that sought to define itself by being against the established norms. It was characterised here in T&T by the spread and the easy availability of marijuana, cocaine, methaqualone (mandrax) and a variety of hallucinogenics. In a publication entitled ‘Cocaine and Heroin Trafficking in the Caribbean’, social scientist Daurius Figueira writes, “Commencing in the late 1960s to the present, Trinbago has been constantly awash in illicit drugs imported into Trinbago from primarily Venezuela. In the late 1960s compressed Columbian ganja and mandrax, manufactured in Columbia, were landed at various points on the coastline and marketed primarily in the East-West corridor of northern Trinidad.”

He goes on to say, “By far the most revolutionary measure undertaken by Government, however, was the introduction of the Police Service Act No. 30 of 1965. Among other changes, the First Division Officers would henceforth come under the general regulations of the Civil Service in regard to certain appointments.” Carr was to serve as Commissioner until 1966, when he would be succeeded by James Porter Reid; he too had been born in Trinidad of an English father and a Trinidadian mother and would serve as Commissioner from 1966 to 1970.

|

| Commissioner of Police James Porter Reid, 1966–1970. |

frustrations felt by a generation of young black people, who in the aftermath of Independence, could not foresee how their hopes and ambitions, that had been inspired by the independence movement, could possible be realised.

The Black Power uprising took place in the wake of labour unrest and strikes during the1960s and events at a Canadian University and were formulated and expressed in the habitual rhetoric of resistance. This language and behavior had its origins in resistance to slavery and later resistance to colonial rule and worker repression, and was seen by many as unfounded because by all intent and purpose the government of the country was a black one. These demonstrations also took shape against the backdrop of world events, not the least of which was the rise of black awareness and the struggle for freedom from tyranny in the United States, South Africa and in other parts of the world where colonial rule, although in the process of passing away, sill lingered, rooted, as it were, in the vested interest of those who still held power.

1970 was a testing year for the Trinidad and Tobago Police Service, with large Black Power street demonstrations, at times numbering some ten to twenty thousand people, on the streets of Port-of-Spain during the months of February, March and April of that year. There was as well a mutiny of the Trinidad and Tobago Regiment at their base at Teteron Bay in Chaguaramas.

Commissioner James Reid’s term of office was due to come to a close at the end of May of that year.

During this period of social upheaval in the black community the post of Commissioner would be filled by Deputy Commissioner of Police Claude Anthony “Tony” May. May, the son of former Inspector-General, Colonel George May, had, like former Commissioner Carr, grown up at St. James Barracks.

Under May’s command, Port-of-Spain, where the marches and the picketing of business places had commenced in February of 1970, was spared rioting and looting. . . “only

The Special Branch had penetrated the Black Power movement and the Trinidad and Tobago Regiment.

The leading personalties of the Black Power movement were Geddes Granger and Dave Darbeau.

|

| Commissioner of Police Eustace Bernard, 1970–1973. |

The Black Power marches and speeches continued to April 20th, 1970. The declaration of a State of Emergency on 21st April, when Granger and some of his lieutenants in N.J.A.C. were detained, brought to an end what was obviously a lawless state of affairs. These detentions marked the end of that phase of N.J.A.C.’s strategy; their objective to bring down the Government of Trinidad and Tobago had failed. Bernard had knowledge that “N.J.A.C. was dominated by people with communist ideas and ideology.” The Police Service had, without a doubt, saved Trinidad and Tobago from what could have amounted to be a foreign power intervention, very likely, according to Kelshall, from Venezuela, or a civil war with all the attendant miseries and violent deaths.

|

| Commissioner of Police Eustace Bernard receives the Medal of Merit from His Excellency, Sir Solomon Hochoy, Governor General of Trinidad. |

|

| Commissioner of Police Eustace Bernard, center, with Superintendents, Inspectors, Sergeants, Instructors and newly graduated constables. |

|

| Commissioner of Police, Claude Anthony May, 1973–1978. |

It was also made clear to the government that this change would eventually cause a backlog in the

|

| Commissioner of Police Tony May with Senior Superintendents, Sergeants and Instructors at the Police Barracks. |

“In so far as security was concerned, having regard to the few men at stations, I have had to withdraw rifles from several stations in Port-of-Spain and place them in central repositories. In several divisions I have had to do the same thing. However, I have not found it prudent to do this with respect to all stations.”

Without the appropriate increase in trained personnel in all ranks, this was a very serious blow to the effectiveness of the Police Service, made critical, by the evidence being collected by Special Branch on the increase of illicit drugs and guns entering the country and, the extent of subversive activities being conducted by persons of interest to the police.

It seems inconceivable that after such a serious social upheaval as N.J.A.C.’s attempt to overthrow

|

| Superintendent Randolph Burroughs. |

The effect of the forty hour work week introduced to the Service by the government brought the now increasingly “at home policeman” into close and personal contact with the expanding drug trade. In the late 1960s–70s, according to social scientist Darius Figueira, “Trinidad and Tobago was fully integrated into the drug trafficking economy of Venezuela.” Bernard claims that the new Regulations “. . . did not permit the policeman to be available at stations for lectures and instructions which, by standing order, are to be given. Since the coming into being of these regulations, there was no one at stations to either to give or to receive

|

| Superintendent Randolph Burroughs with members of the “Flying Squad” who are receiving instructions on the use of metal detectors. |

The change in working hours had created circumstances that could only be described as very serious with regard to conflicts of interest. Loyalty to the Service and performance of duty were conflicted with the appearance of illicit drugs, with personal, family and community concerns. The forty hour work week especially affected the probationer and those who had recently joined the Service: compromised in their loyalty, they were often forced to turn a blind eye to what they saw taking place in their homes, amongst their friends and in the community that they grew up in. Ironically the number of arrest for possession of marijuana increased dramatically generating long trial delays and overcrowding in the Remand Yard.

As marijuana became the popular drug for recreation and anti-social behaviour, it was only a matter of time before the real purpose of its introduction began to manifest, which was to facilitate the importation and transshipment cocaine, accommodate money laundering and the introduction of guns and ammunition. White-collar crime would take root in certain businesses and in several government departments so as to facilitate the drug trade.

The forty hour work week, introduced by the Welfare Association and accepted and implemented by the government, as sudden as it was, served to create a breakdown in discipline and compromised loyalty to the Service. It generated, in the long run, the backlog of cases in the courts and eventually the overcrowding and near collapse of the prison system where, in the remand yards, a university for criminals was created.

These events were further exacerbated by the emigration of some one hundred and ten thousand people who left Trinidad and Tobago from 1960 to 1970; about one tenth of the population. In the previous period, 1950 to 1960, just four thousand people had emigrated. This emigration was both a loss culturally and a loss intellectually, as many of these were urban dwelling secondary school educated. (The population of Port of Spain in the 1960s-70s stood about 100,000, it is now perhaps 25,000) It left many children and young people without parents, exemplars and proper guidance. Without a doubt the society was undergoing a fundamental change, an exodus, in fact, as in the following twenty years, over one hundred seventy thousand persons would leave Trinidad and Tobago to seek their fortunes abroad, producing a generation of the so called “barrel children”. Children whose only contact with their parents were the barrels of gifts received by them from time to time. To have an idea of what segment of the population that was in the majority of this exodus is to note that carnivals appeared in Brooklyn, London, and in Toronto, as well as in other places.

The corollary to the emigration phenomenon was immigration. This saw about the same amount of people, all from the other islands, come to this country, as those who had left it. These were mostly primary school educated, if at all, and lived increasingly in scattered squatter communes along the east-west corridor and in the older neglected and impoverished areas, both in the east and to the north-west of the city of Port-of-Spain.

|

| Commissioner of Police Randolph Burroughs, 1978–1987. |

Former Commissioner of Police Bernard in his book ‘The Freedom Fighters’ relates, “Many of them would meet regularly at the corner of Panker St. and Bay Road in St James.” It would appear that these meetings, monitored by Special Branch, attracted a following that included former soldiers, petty criminals, weed pushers, and ex Queen’s Royal College students, some of whom had failed in their scholastic endeavours. Bernard describes them as coming from the surrounding areas of Woodbrook, Khandahar St., Bellevue, Diego Martin, Belmont, Debe and Boissiere Village. An influential personality in these meetings was a young man by the name of John Bedeau. (A coincidence of history gives him the same name as the mulatto ship’s captain, Jean Bedeau, of the French Revolutionary period that Colonel Picton fought against.)

Bernard writes, “He, Bedeau, unlike the non-achievers was, by comparison, well qualified having got his ‘A’ levels and was employed. He was their age, articulate, persuasive, mild of temperament, but a born revolutionary.” He provided the group with books and instructions on revolutionary tactics. The other influential members of this core group was Guy Harewood, who came from an upper-middle-class background, and Brian Jeffers, a drug pusher and petty criminal. It was agreed that N.J.A.C.had failed because of the absence of military muscle. The ‘Brothers’, as they called themselves, decided to create an organisation that would seize the country by force of arms, a notion that was fortified by the number of former regiment men who were in sympathy with their ideals. They would call the organisation the National United Freedom Fighters, N.U.F.F.

|

| Commissioner of Police, Randolph Burroughs, in consultation with former Commissioner of Police, Mr. Tony May during the N.U.F.F. insurgency. |

The National United Freedom Fighters, N.U.F.F., evolved into a highly organised and very motivated band of young men and women who staged several bank robberies and holdups, executed acts of sabotage against vital installations, bombed homes of Regiment Officers, ambushed police patrols, shot and killed civilians, destroyed police stations, attempted the murder of Captain David Bloom, and killed four policemen, wounding several others in the course of their duties.

Those murdered were: Constable McDonald Pritchard, Constable Austin Sankar, Corporal Bascombe, and Corporal Andrew Britto.

In the face of almost daily assassination attempts and brazen robberies, all coming in the wake of the harrowing period of the N.J.A.C./Black Power uprising and attempted mutiny by elements of the Defense Force, it became clear that a new and challenging period was upon the Service.

|

| Commissioner of Police Randolph Burroughs inspects a detachment of Women Police Constables at the passing out parade, St James Barracks. |

Bernard informs us that Randolph Burroughs was an indefatigable worker. He was “most loyal to his seniors and his country, and most importantly, the best informed man of his time on criminals and their activities. He had enlisted in the Service in 1950. He had served most of his service in the Criminal Investigation Department and was cited for outstanding work on twenty three occasions.”

In 1972 after a shootout with Police and a party of well armed and obviously motivated men on the Blanchisseuse Road, Commissioner Bernard relieved Superintendent Burroughs of all other duties and directed that he concentrate on the apprehension of those responsible for what was feared to be an incipient guerrilla movement that was being motivated and guided by outside interest that had as their intention the overthrow of the Government. It was feared that this situation could grow and evolve into a full scale conflict, that in the worsening financial state of the country (this was before the oil boom of 1973) would tend to attract those who had been motivated by the Black Power movement, dissidents, Cuba inspired trade unionists, former members of the Regiment, criminals, the generally disaffected, the impoverished, the desperate and even the idealist.

|

| Commissioner of Police Randolph Burroughs was awarded the Trinity Cross. He seen here with Commodore Mervyn Williams also a recipient. |

During the following three to four years, the Flying Squad was engaged in running battles with the N.U.F.F. that took place in forested areas of the northern range, in towns and in fact across the country. The robberies of banks and other places provided the N.U.F.F. with cash, but it became obvious to the police that they were being guided and supplied increasingly with sophisticated weapons, cocaine and marijuana.

|

| Commissioner of Police Randolph Burroughs as opening batsman. |

Commissioner of Police Randolph Burroughs’ term of office came to an end in 1987. He was succeeded by Commissioner Louis Jim Rodriguez.

|

| Commissioner of Police Louis Jim Rodriguez, 1987–1990. |

In 1990, partly as a result of political indecisiveness, a breakdown in communications and against a protracted downturn in the economy, yet another insurgent group arose. Its alleged purpose was to resist political chicanery, wanton social injustice and exploitation of the disadvantaged. Muslim extremists were able to train and indoctrinate a membership, evade detection and import a quantity of explosives, arms and ammunition. They destroyed by fire the Police Headquarters on St. Vincent Street, Port-of-Spain, murdering the sentry on duty, while holding the members of the Parliament of Trinidad and Tobago hostage and causing multiple deaths in another attempt to overthrow an elected government. These events took place in the first year of Commissioner of Police Jules Bernard taking office.

|

| A tense moment as Commissioner of Police Rodriguez makes his way to attend a funeral for a fallen comrade. Note the police officer standing behind the irate civilian. |

|

| Commissioner of Police, Louis Rodriguez, middle with uncrossed legs, with First Division officers. On his left is Deputy Commissioner of Police Jules Bernard, his successor. |

In 2004, we designed and built the Museum of the Trinidad and Tobago Police Service in Port of Spain. Click here to look at pictures of the exhibit.